IS THAT “ALL THERE IS TO THAT?”: The Character of Billy Bigelow

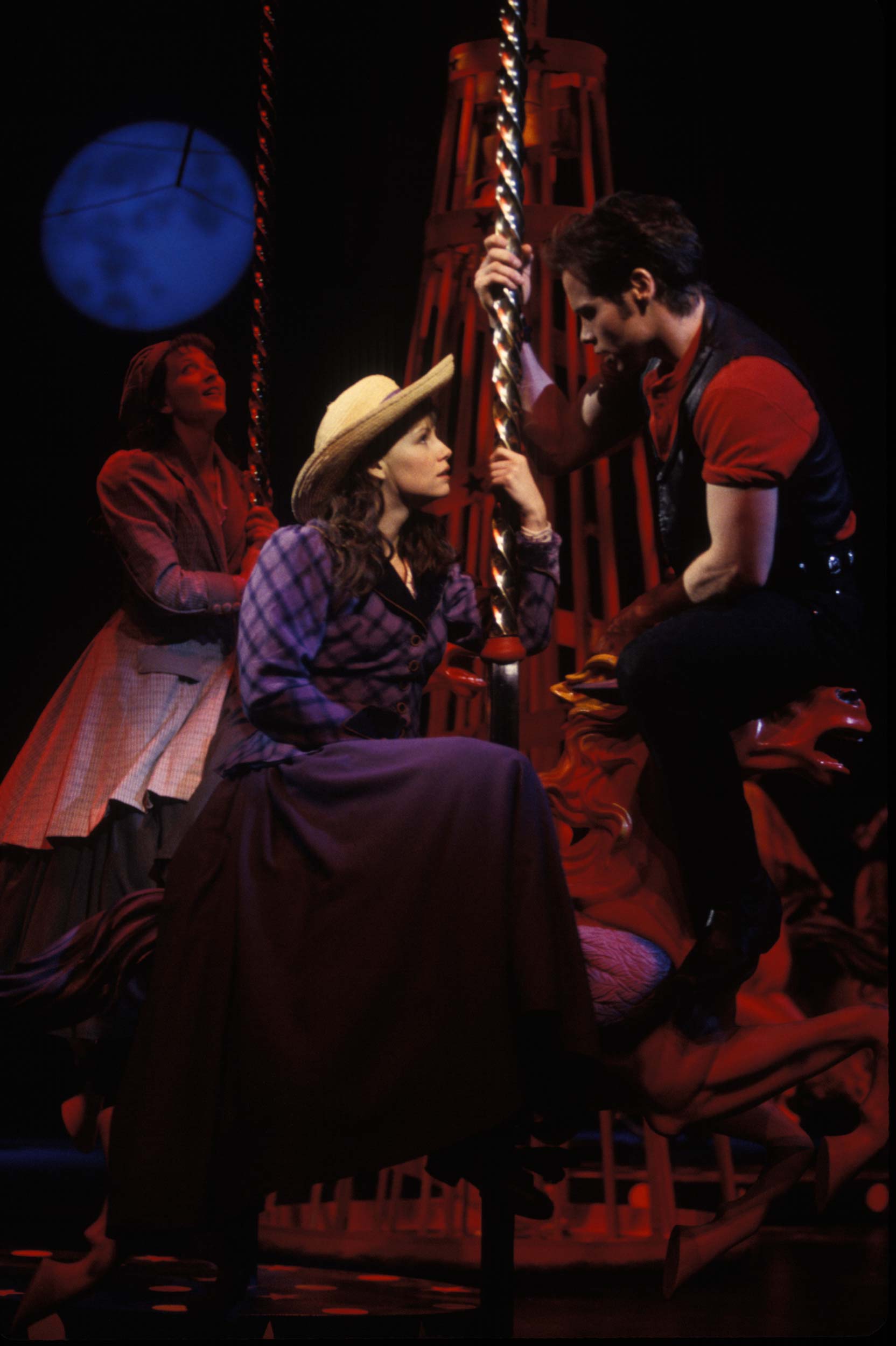

The moment when Julie Jordan and Billy Bigelow first really “connect” in Carousel comes when the merry-go-round itself is just about to twirl – “Billy laughs and lifts her up, onto the last remaining horse.” Their relationship in the musical is equally dizzying. It is also potentially disorienting, particularly for modern audiences who are affected by the portrayal of domestic violence that is at the dramatic core of Billy Bigelow’s character.

Domestic violence can never be condoned or ignored. Still, it is worth looking at how Carousel positions domestic abuse without condoning it but also how the musical frames the character of Billy Bigelow within the context of its story. Like the carousel itself, that context whirls as a series of circles within concentric circles.

The first, and perhaps largest, circle is the source material for Carousel: Liliom, written in 1909 by the Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnar. The original play sprang from the fertile theatrical mind of Molnar, who frequently mixed tragedy and farce in his plays and was equally adept (along with his contemporary, Luigi Pirandello) at adding fantasy to his scenarios and breaking the “fourth wall” by acknowledging theatrical conventions within the plays themselves (we’d call this “meta” now). In its initial Hungarian production, Liliom was considered to be too fast and loose with accepted dramatic conventions: was the concept of its lead character coming back from the dead to redeem the bad choices made during his lifetime supposed to be morally uplifting or simply cynical?

Still, the play became a critically acclaimed hit when it was eventually produced on Broadway in 1921 (and again in 1940); Orson Welles, in a 1939 radio adaptation of the play, called Liliom “incredibly beautiful and beautifully incredible.” The English-language translator of Liliom, Benjamin Glazer, wrote “something happened after [World War I] that allowed audience to appreciate such ambiguity.” Perhaps one of the elements that made for a deeper connection to audiences was the play’s darker side. “Liliom” is the name of the title character – a nickname actually, meaning “one who wears a lily,” which could mean for fashion, or for a funeral – and, like Billy Bigelow, he works for a carnival and has an egotistically callous nature.But the original play is set in the capital of Budapest of 1909, not in a charming seaside town in Maine. It is an urban setting, full of gritty, often violent characters. There is a robbery attempt at knifepoint; a suicide (which would have a much more negative connotation in a Catholic country such as Hungary); casual cruelty among the characters; a cynical and detached police force; intimations of anti-Semitism (the victim of the attempted robbery is Jewish); and a general sense of dog-eat-dog in this environment. As Glazer put it in an introduction to the published version: “Perhaps Molnar was at the old, old task of revaluing our ideas of good and evil. Perhaps he has only shown how the difference between a bully, a wife-beater and a criminal on the one hand and a saint on the other can be very slight. If Liliom has a moral, it might be in [the lead character’s] dying speech to Julie: ‘It’s all the same to me who was right. – It’s so dumb. Nobody’s right… but they all think they are right… A lot they know.’”

Domestic violence can never be condoned or ignored. Still, it is worth looking at how Carousel positions domestic abuse without condoning it but also how the musical frames the character of Billy Bigelow within the context of its story. Like the carousel itself, that context whirls as a series of circles within concentric circles.

That’s a pretty bleak moral for a musical – especially for one written in 1944-45, when America was trying to beat back fascism across the globe. This brings us to the next concentric circle: the changes that Hammerstein made with his adaptation of the original play. Reportedly, it was Richard Rodgers who suggested resetting the play decades earlier in a seaside New England town (neither collaborator was interested in keeping the musical adaptation set in Budapest). An American setting, a chronological distancing, the addition of song-and-dance – all of the choices made the atmosphere of Carousel brighter and more accessible than the original material – even while the songwriting team kept the tension from the original play simmering underneath.

Within the narrative of Carousel, the violence inherent in the source material waits in the wings nervously for its entrance. But it does arrive and it arrives quickly. During the first few scenes, we observe the aggressive nature of some of the musical’s characters and their situations. Mrs. Mullin, the carousel owner, is hardly demure or respectful towards Julie – whom she sees (shrewdly) as a threat to her own (dysfunctional) romantic relationship with Billy – or to Billy himself. She threatens to toss Julie “right out on [her] little pink behind” if she catches her at the carousel again. Mrs. Mullin, in a fit of fury, also fires Billy from the carousel and invokes the spirit of her late husband – clearly also a violent man: “He’d give you such a smack in the jaw!” To which Billy replies, “That’s just what I’m going to give you, if you don’t dry up!”

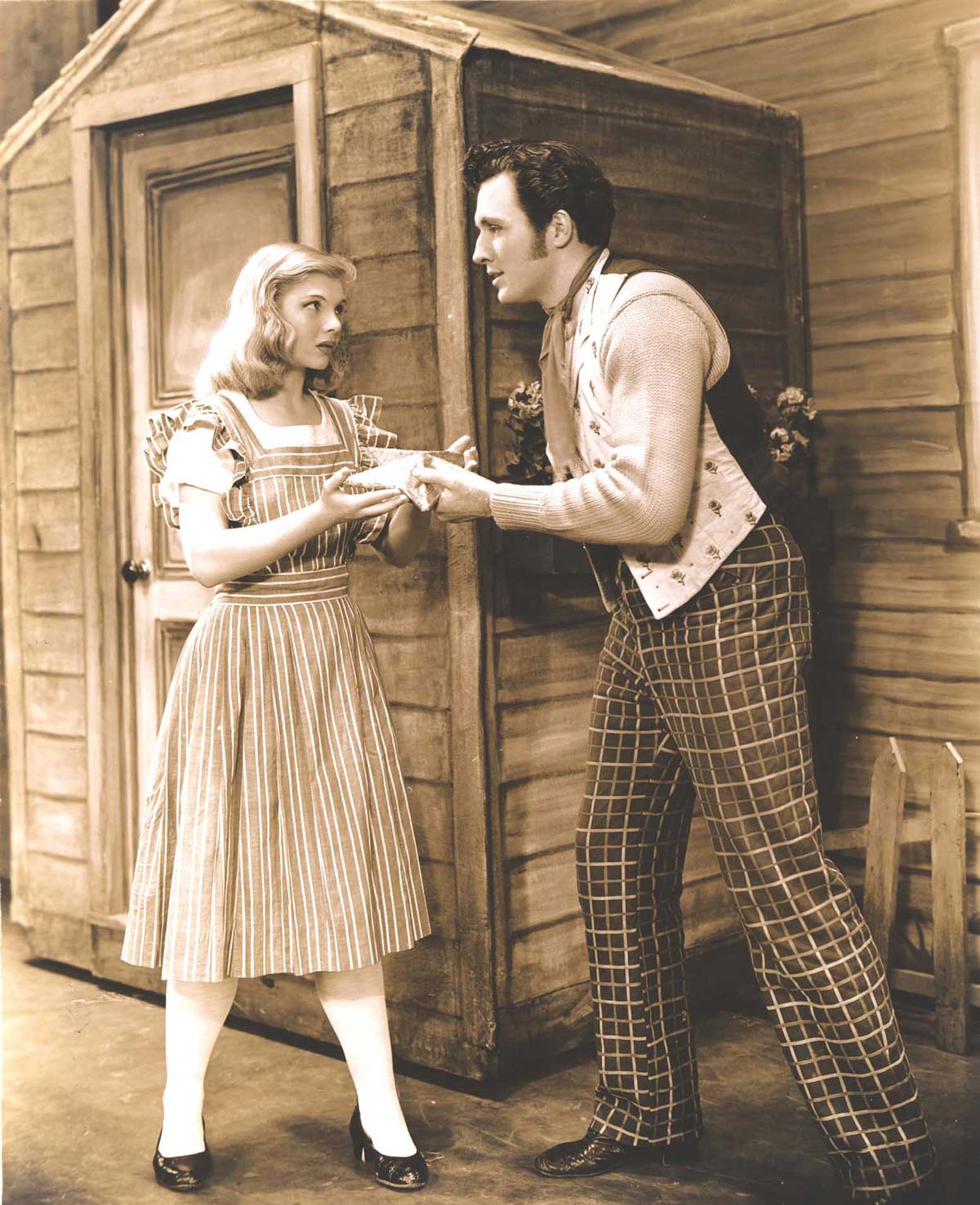

In Billy’s subsequent scene with Julie – after having also been derided a “scalawag,” a “bounder,” and a “gazaybo” (whatever that is) by a condescending policeman and a snobbish local mill owner – he reveals that there is a tender side to him, underneath the armor of his polished egotism. The “bench scene” with Julie (as it’s known) opens an important window into Billy’s soul and it’s an essential moment for the audience: by the next time they see him, the audience will need to know that Billy is capable of higher, better things.

The trope of a leading character whose brutality is baked into their personality is a persistent one in popular books, plays and movies.

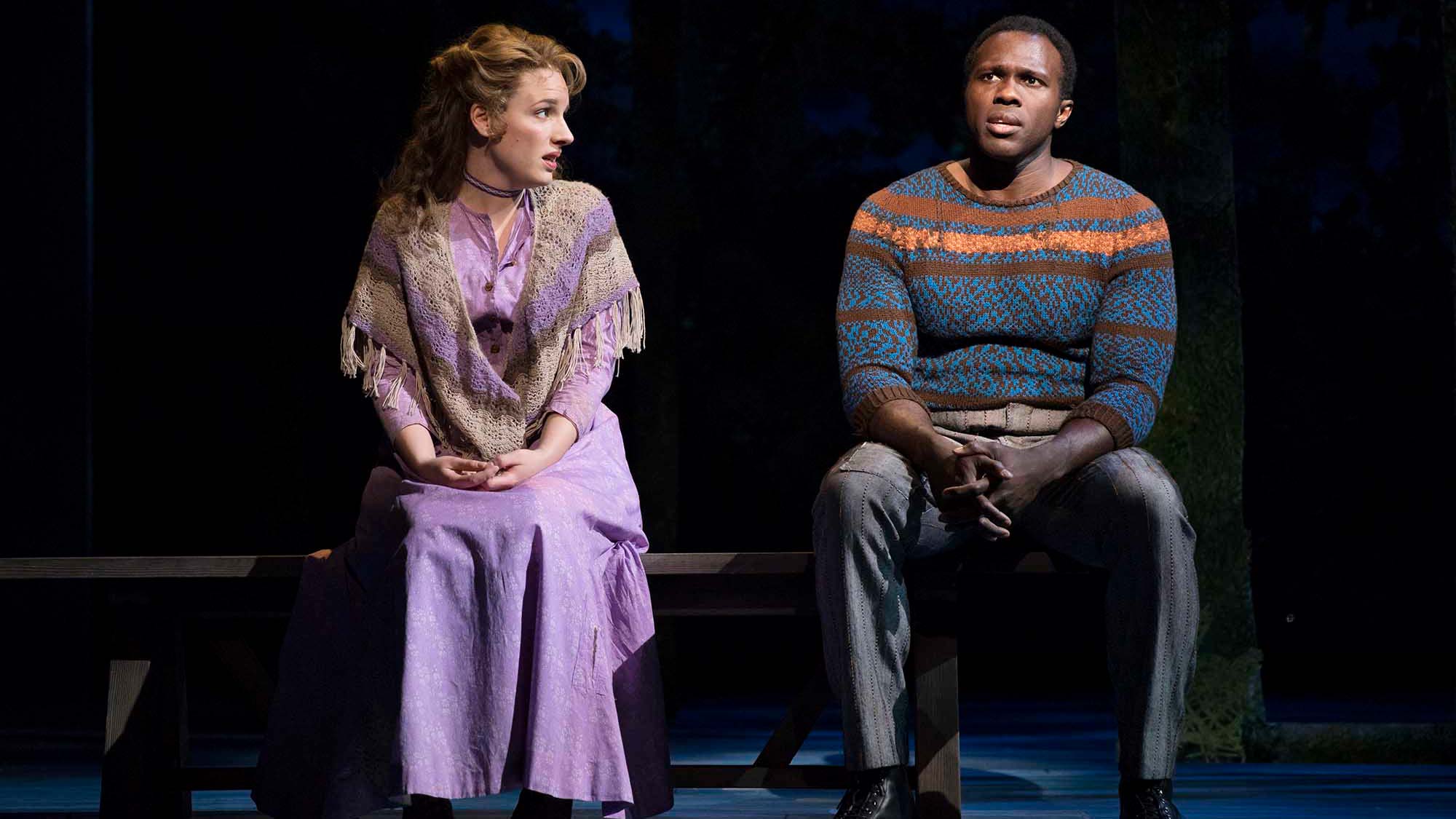

The next important plot point was inherited by Hammerstein from Molnar and he kept it nearly intact. It’s a month later: Julie and Billy are married and are living with her cousin. Billy’s been out of work and spending what little money they have in bad company; he listens balefully from afar to the carousel music. And he’s hit Julie. Her friend Carrie initially appears solicitous (easier for her, because she has conveniently arranged her own marriage to a respectable citizen with a respectable business) but affects to be appalled at Billy’s violence: “I’d leave him. Thinks he can do whatever he wants because he’s Billy Bigelow.” However, Julie still loves her husband; she accepts that his own frustration causes him to lash out at her. And it’s that twinned action and response that has made Carousel problematic in a modern world: first, that Billy hits his wife and, second, that his wife finds it tolerable. Billy’s violent nature is acknowledged and accepted by Julie several more times in the musical, mostly lyrically in her song. “What’s the use of won’drin’ if he goes or if he’s bad. / He’s your fella and you love him – that’s all there is to that.” Yet, Hammerstein gives Billy several opportunities to reveal a more vulnerable side, particularly in the remarkably expansive “Soliloquy” toward the end of Act 1.

The relationship between the leading characters in Molnar’s original play provides a stark contrast with the musical. Liliom’s behavior is even more unacceptable and Julie’s reaction to it is even more tolerant – “co-dependent,” we might call it now. When Liliom descends from the Heavenly Court and offers a stolen star to his daughter as a way of making amends for his behavior, he slaps her for rejecting it; he has tossed away his second chance, essentially losing his appeal to the Court, and is dragged away. Julie responds to her daughter’s bewilderment by, essentially, doubling down on her devotion to Liliom, despite his incorrigible insensitivity: “It is possible, dear – that someone may beat you and beat you and beat you – and not hurt you at all.” As expressed, this juxtaposition remains too brutal for the world of Carousel.

The trope of a leading character whose brutality is baked into their personality is a persistent one in popular books, plays and movies. There are numerous characters who make their living in a boxing ring – to use one frequent example – and must wrestle with how that arena exploits their violence while numbing their souls: Robert De Niro’s Jake La Motta in Raging Bull or Rocky Balboa. We see it repeated with gangsters like Michael Corleone in The Godfather or Tony Soprano; Marlon Brando’s character Terry Malloy in On The Waterfront works on the fringes of both boxing and the mob. The character who most completely embodies this popular archetype is another Brando creation: Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, who met Broadway audiences in 1947, two years after Carousel opened. Kowalski is a domestic abuser, a self-centered lout who lashes out at everyone – and yet his wife loves him deeply despite his worst offenses; the paradox of Kowalski’s character is a cornerstone of modern drama.

In musicals, however, such a blatant “anti-hero” was a rare sight and a seeming contradiction with the form. Back in 1940, Rodgers himself, along with his first partner Lorenz Hart, had given Broadway Joey Evans in Pal Joey; an ethically challenged gigolo, Joey was shocking to many members of the audience. But Oscar Hammerstein was always determined to take the musical form to another, more dramatic place – he nearly always chose the more complex solution to any problem. In the case of Billy’s character, Hammerstein embraced a concept that Molnar rejected in the original: redemption – that most spiritual of ideas.

Hammerstein, a lifelong creature of the theater, could easily see the appeal of a ne’er-do-well like Joey Evans, but he was much more interested in portraying a ne’er-do-well who eventually does well. Having failed at his second chance at a reprieve, Molnar’s Liliom gets dragged away – effectively condemned by the Heavenly Court. Hammerstein’s Billy, on the other hand, is given a third chance. As a spectral figure, observing his daughter’s graduation, Billy urges his daughter to believe in her aspirations. He also affirms a deep love for his devoted wife – articulating something he could never say in life. In the end, Billy is led back to “Up There” (as Hammerstein calls it) with the assumption – presumption, perhaps – that his time on earth has not been a waste, that he has redeemed himself. This is the drama of transformation – and a character can only transform in a meaningful way if he or she has been initially set up with flaws and defects – and goodness knows those flaws have been portrayed in the character of Billy Bigelow.

There are elements of Carousel that will inevitably disturb members of a modern audience – we are far more aware of the depths of domestic violence and the #MeToo movement has been a seismic shock to our social system, awakening our recognition of the indignities that have existed in our culture for a long time. In a 2018 essay for the Nation, critic Alisa Solomon wrote, “[Carousel’s] central arc needs fresh framing if a contemporary audience is to engage with it wholeheartedly. The difficulty isn’t only that Billy hits his wife and that she rationalizes his violence in dialogue and in [‘What’s the Use of Wond’rin’]. We know, alas, that such dynamics persist in abusive relationships.”

Acknowledging those issues, though, we can frame Carousel’s story within some concentric circles. The first is the gritty side of the original Liliom. It was groundbreaking for Hammerstein to take two such complex characters and put their relationship at the center of an entertaining popular artform such as the musical. We can still feel where Molnar’s shades of darkness conflict with Hammerstein’s forces of optimism; perhaps a darker, more modern musical treatment would allow audiences to see the violence of the original as more organic to the piece. The second circle is Hammerstein’s use of love as a redemptive force for the character of Billy Bigelow. The writer does not condone Billy’s violence, but neither does he omit it from the story because his version of the carnival barker embraces a longer, more transformative journey; his Billy must begin at an unacceptable place in order for his redemption to be resonant. And, finally, in its widest circle, Carousel whirls around in a modern world, a work of art with roots more than a century old, still meaningful and moving to audiences – even with its flash points of discomfort and disapproval – because its characters and their dilemmas are eternally without closure, just as we are, in the circular revolutions of our lives.

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.