I AND THE KING: A Delicate Balance

As a sign of its serious intent, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s The King and I concludes with a deathbed scene and a change in dynasties, as the eponymous king bequeaths a new regime to his heir. The off-stage history of The King and I also had a deathbed scene, and in this case, one leading actor bequeathed her star power to another.

In the spring of 1951, Gertrude Lawrence had originated the role of Mrs. Anna in The King and I opposite Yul Brynner; by the fall of the following year, she was hospitalized with a swift and fatal bout of liver cancer. While on her deathbed at New York Hospital, she left instructions for her agent, Fanny Holtzmann: “About the play—see that Yul gets star billing. He has earned it.”

And so began a dynastic tradition, a passing of the torch, back and forth, forth and back between the supremacy of the leading roles of King Mongkut and Mrs. Anna Leonowens.

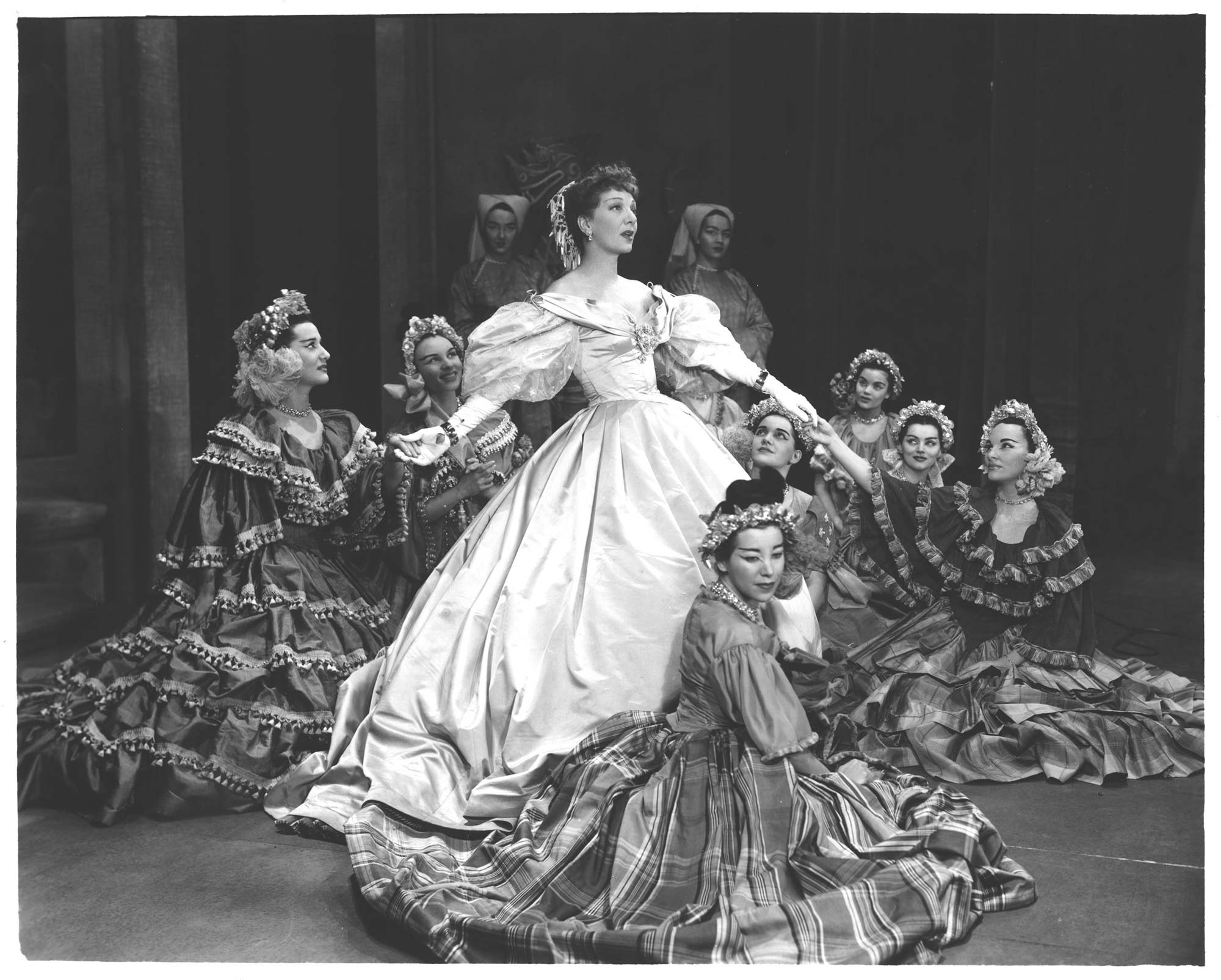

As the 1940s were coming to a close, Gertrude Lawrence reigned as one of the most incandescent stars of the Broadway scene. The London-born performer had become a Broadway luminary in the mid-1920s, starring in the Gershwins’ Oh, Kay! (she introduced “Someone to Watch Over Me”), followed by a series of triumphs in various plays and revues written for her by an old chum for her child actor days in Britain—Nöel Coward. Lawrence was the avatar of glamorous sophistication—a quirky, mercurial, light-hearted sensual redhead with the ability to make you laugh and break your heart—often simultaneously. She began the 1940s by playing the glamorous lead in Lady in the Dark for over two years and finished out the decade with a triumph as Eliza Doolittle in a revival of Pygmalion, even though she was three decades older than the character.

She also had a formidable lawyer named Fanny Holtzmann who represented such varied and powerful clients as Coward, Fred Astaire, the deposed Russian royal family, and Chiang Kai-shek. In 1950, she was approached by the William Morris Agency to see if she would be interested in the stage rights to Margaret Landon’s novel based on the real-life memoirs of Anna Leonowens, called Anna and the King of Siam. The work had already been adapted as a film starring Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison a few years earlier in 1946, but a stage version could be an attractive property—especially if Gertrude Lawrence played the lead.

In the spring of 1951, Gertrude Lawrence had originated the role of Mrs. Anna in The King and I opposite Yul Brynner; by the fall of the following year, she was hospitalized with a swift and fatal bout of liver cancer. While on her deathbed at New York Hospital, she left instructions for her agent, Fanny Holtzmann: “About the play—see that Yul gets star billing. He has earned it.”

Holtzmann and Lawrence instantly realized the musical potential for this material and, after some fits and starts, Holtzmann reached out to Oscar Hammerstein II. The exotic locale, the potential dramatic conflict between the two leads, the opportunity to demonstrate a serious message about cultural values—all of it appealed to Hammerstein. Richard Rodgers, not so much: “While we both admired Gertie,” he wrote, “we thought her vocal range was minimal and she had never been able to overcome an unfortunate tendency to sing flat.” But Gertrude Lawrence came along with the project, like it or not, and—after screening the film a few times—Rodgers & Hammerstein wound up liking it a lot.

Contracts were signed with Lawrence in the summer of 1950, which gave the team plenty of time to write the script—and to find a suitable king to match Lawrence’s stage majesty. Rodgers & Hammerstein (who were now also sole producers) reached out to the movie’s King, Rex Harrison, who turned the project down. They briefly considered Nöel Coward—Lawrence’s most frequent and legendary stage partner—but felt their past associations in witty drawing room comedies and light revues would confuse audiences. Alfred Drake, who back in 1943 had led the company of Oklahoma! and was now, after Kiss Me, Kate, a full-fledged star, seemed interested, but ultimately passed; Rodgers would go on to suggest the rejection was about money, but Drake, privately, was also concerned about his co-star’s musical unreliability.

Pretty much stuck, the songwriting team had to consider an actor who might not be a big name but could still carry the weighty part on his shoulders. Their colleague Mary Martin urged them to audition an actor who had played opposite her in a Chinese-set drama called Lute Song a few seasons earlier. Born in Vladivostock, of a varied background of Russian, Mongol, and Swiss descent, the actor had transitioned into a career as a television director in New York City. His name was Yul Brynner and he seemed to be an unlikely candidate. Still, Mary Martin kept pushing and, after all, they did need to find an eponymous king. As Rodgers famously recounted about Brynner’s audition, “He had a guitar and he hit his guitar one whack and gave out with this unearthly yell and sang some heathenish sort of thing. Oscar and I looked at each other and said, ‘Well, that's it.’” They signed Brynner for about $300 a week, a fraction of what Lawrence was making and barely more than his TV gigs were paying. And he was billed far below Lawrence on the show’s poster, at about 1/3 the size of her name: “I and The King” indeed.

They signed Brynner for about $300 a week, a fraction of what Lawrence was making and barely more than his TV gigs were paying. And he was billed far below Lawrence on the show’s poster, at about 1/3 the size of her name: “I and The King” indeed.

Still, the onstage relationship between Lawrence and Brynner proceeded smoothly throughout the tryout of the show in the winter of 1951. The role was proving taxing to Lawrence—she missed some of the New Haven run with laryngitis—but Brynner was supportive, and by the time the second act song, “Shall We Dance?” was added and polished by choreographer Jerome Robbins, the musical had the aura of a hit. There had been some cavils among theater wags—was Lawrence too old-fashioned for this new kind of narrative musical? Was she jealous of how exciting Brynner was proving with audiences? Was she up to the immense challenges of the show, corseted as she was, literally, by a 30-pound hoop skirt?—but by opening night, March 29, 1951, Lawrence was in command, in lockstep, with her equally commanding (and demanding) King.

The show was a smash; it made Brynner into a star overnight. Both Lawrence and Brynner won Tony Awards for their work; she for Leading Actress, while he won for Featured Actor in a Musical—another example of the perceived professional imbalance in their work on the show. Lawrence, buoyed by her two-year contract, entertained dreams of playing Mrs. Anna in the West End. However, she was getting increasingly ill, asking for time off to rest or requesting a vacation (she was briefly replaced by Celeste Holm). Rodgers & Hammerstein were not pleased—Lawrence was a star and a star’s absence means a dip in the box office. Despite Lawrence’s illnesses and ongoing pitch problems, audiences were still captivated. Her director, John Van Druten, wrote, “The star quality was there—that indefinable but intensely vivid sensation that comes from something other than the technical or human talents of the actress, giving her an iridescence. Whether Gertie was giving a good performance or a bad one, that radiance was always there.”

But that radiance began to dim; Lawrence was hospitalized more than a year into the run and diagnosed with liver cancer. She died on September 6, 1952, three weeks after playing her final performance at the St. James Theater. Coward eulogized her in the London Times: “An analysis of her talent, however, would require a more detached pen than mine. I could never be really detached about Gertie if I tried to the end of my days… Her quality was, to me, unique and her magic imperishable.”

Rodgers & Hammerstein still had a hit on their hands, however, and it needed attention—and a little sprinkling of stardust. When Brynner took a brief vacation in 1953, his replacement was Alfred Drake; toward the end of the run, Mrs. Anna was played by Drake’s costar from Kiss Me, Kate, Patricia Morison. By then, however, Brynner was leading the national tour and, for the first time, he received star billing, solo, above the title (Lawrence’s understudy, Constance Carpenter, was playing Mrs. Anna and her billing was in smaller type below the title, just the way Brynner had been on Broadway).

The tour was a phenomenal success (Morison joined it at one point and was given star billing—but second to Brynner’s). It was only a matter of months before Hollywood beckoned, offering Yul Brynner not one, but two, crowns. Legendary director Cecil B. De Mille (uncle of Agnes) offered Brynner the starring role of the pharaoh Rameses in his upcoming epic The Ten Commandments; it would have been Brynner’s Hollywood debut, but for the fact that the movie took so long to make that he was able to start filming on The King and I-–and have it released—before The Ten Commandments opened on screens across the country in October of 1956.

As is usual with a Hollywood adaptation of a Broadway musical, there were a fair number of hoops (or hoop skirts) that had to be jumped through before shooting on The King and I started. Before Brynner was cast to reprise his stage role, there was a little noise about hiring Marlon Brando for the part, but in the mid-1950s, Brando was mentioned for every part in the movies; Brynner’s natural film presence and the fact that he was a relative unknown to mainstream audiences only accrued to his appeal—he was a shoo-in. Fiery film actress Maureen O’Hara was seriously considered to play Mrs. Anna by Darryl Zanuck, the head of 20th Century Fox (they had produced the earlier non-musical version of the story), bur Rodgers vetoed her. Her replacement, Deborah Kerr, a poised British beauty—and a bona fide movie star to boot—was an ideal choice and Brynner was supportive of her both before and during shooting; they apparently got along famously. Kerr said of her king: “He has such respect for actors and what they do. He single-handedly turned what might have been an average Hollywood musical into a great film.”

Kerr’s considerable body of work (she had made two dozen movies before The King and I) guaranteed her top billing in the film, but the 1956 CinemaScope epic had enough success to go around; it was nominated for nine Oscars (including Best Picture and Best Actress for Kerr) and won five—particularly one for Brynner as Best Actor, “featured” be damned. Six months after The King and I was released, The Ten Commandments hit the screen; by the time 1956 had concluded, Yul Brynner had parlayed his pair of kings into a majestic screen career. He was now a star of the first rank.

Over the next two decades, Brynner cultivated the personality and the perquisites of an international film star. It is difficult, at the remove of more than half-a-century, to contextualize how unique and appealing Brynner was to millions of fans. His bald pate became a worldwide trademark—as a punchline for some, but a gleaming erotic beacon for others. His exotic background—which Brynner often obfuscated for effect—also allowed him to play parts that more ordinary actors couldn’t touch. He was also fiendishly talented. But his international lifestyle—wives, girlfriends, expensive homes, expensive tastes, a multi-pack-per-day smoking habit—often got him into financial trouble. By the early 1970s, he realized that he held a valuable asset in reserve: his legendary identification with the role of the King of Siam. Brynner set about monetizing that connection with a vengeance.

The first attempt was an ambitious but brief television series called “Anna and the King,” co-starring Samantha Eggar, which didn’t make it through the 1972 season. But Brynner wisely realized his King belonged on a theatrical throne. Aside from a few television variety performances, New York hadn’t seen Brynner’s King in almost a quarter-century—and a lot had happened since. Successful revivals geared to legendary performers playing their signature roles had become a profitable enterprise on Broadway—especially when they could tour the country before and/or after—and Carol Channing (Hello, Dolly!) and Zero Mostel (Fiddler on the Roof) had paved the way.

Brynner arrived back on Broadway in May of 1977; this time, his face was a mile high on the poster and his Mrs. Anna, the talented Constance Towers, below the title and in smaller type. His year-and-a-half reign at the Uris Theater was a triumph, and to say that Brynner lived like a king would be too obvious a simile. He had his dressing rooms (both on Broadway and on the road) tailored to his precise and particular requirements (painted chocolate brown, for example) and his three-part curtain call was its own set piece (woe to the audience that did not submit with an immediate standing ovation). He also took on the role of co-producer, which was a mixed blessing—he made money be-ringed hand over fist, but could never miss a performance or offer up a lazy one; it would cost him profits in the end.

But the money was there, providing a virtual red-carpet runway for Brynner. Five years after his first Broadway revival closed, he started another tour. This version eliminated any pretense of equanimity; Brynner’s name was bigger than the title and the television commercials nearly eliminated his Mrs. Anna, Mary Beth Peil. “The King is Back!” read the advertisements, and that was all customers needed to know. But the last hurrah at the Broadway Theater in 1985 was an arduous one; it followed an extensive tour and by then Brynner himself had contracted lung cancer, a condition he carefully parsed out to the media in the form of an anti-smoking message. His illness seriously affected his performances; he often skipped over his big solo, “A Puzzlement,” and required constant support from his co-stars. Still, when he flung his arms wide apart, basking in adoration for his final curtain call on June 30, 1985, it was a legendary feat of noblesse oblige. Yul Brynner had played the King of Siam 4,625 times onstage. It was a record for its time. (Twenty years later, Carol Channing would go on to beat his record, performing in Hello, Dolly!, but as she said, “I just loved Yul Brynner, I adored him, so when I hit five thousand performances, I’ll never tell anybody. I don’t want him to roll over in his grave.”)

Brynner would pass away a little over four months later; like his first co-star, Gertrude Lawrence, his final project would be The King and I and cancer would be the reason for his mortal demise. Still, the end of Brynner’s personal dynasty did not spell the demise of the show itself. The King and I has whistled its own happy tune through numerous subsequent productions around the world and on Broadway, in acclaimed revivals both in 1996 and 2015. Talented stars such as Rudolph Nureyev, Angela Lansbury, Donna Murphy, Daniel Dae Kim, Marin Mazzie and Kelli O’Hara (who won her first Tony Award playing Mrs. Anna in 2015 Lincoln Center Theatre production) have taken on the mantles of Mrs. Anna and the King in various productions, but the chemistry between the two roles is a delicate balance.

One of the most thrilling aspects of any successful production of The King and I is the battle of wits between Mrs. Anna and the King: Who will come out on top? In its 70-year professional journey, that battle has been joined, not only onstage, but offstage in countless posters, Playbills, production credits, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.