THE TRAPP FAMILY SINGERS: THE SOUND OF THEIR MUSIC

For a while there, it looked like The Sound of Music was going to be Broadway’s first jukebox musical.

It only made sense. The jukebox musical, as it’s come to be known, is a theatrical genre that takes a popular singer or singing group and frames their biography around a narrative show of some kind which features their biggest hits: Jersey Boys, say, tells the story of the Four Seasons in the 1950s and ‘60s by reframing their most famous songs as biography; the same thing with Ain’t Too Proud and the hits of the Temptations.

And, of course, The Sound of Music is essentially framed around another successful singing group, known originally as the Salzburg Trapp Choir and then, more famously, the Trapp Family Singers. The family at the center of the musical by Lindsay & Crouse, Rodgers & Hammerstein was a real—very real—singing group that had an extraordinary origin and an impressive professional career, in Europe and in America, with a various recording contracts and a dedicated fan base.

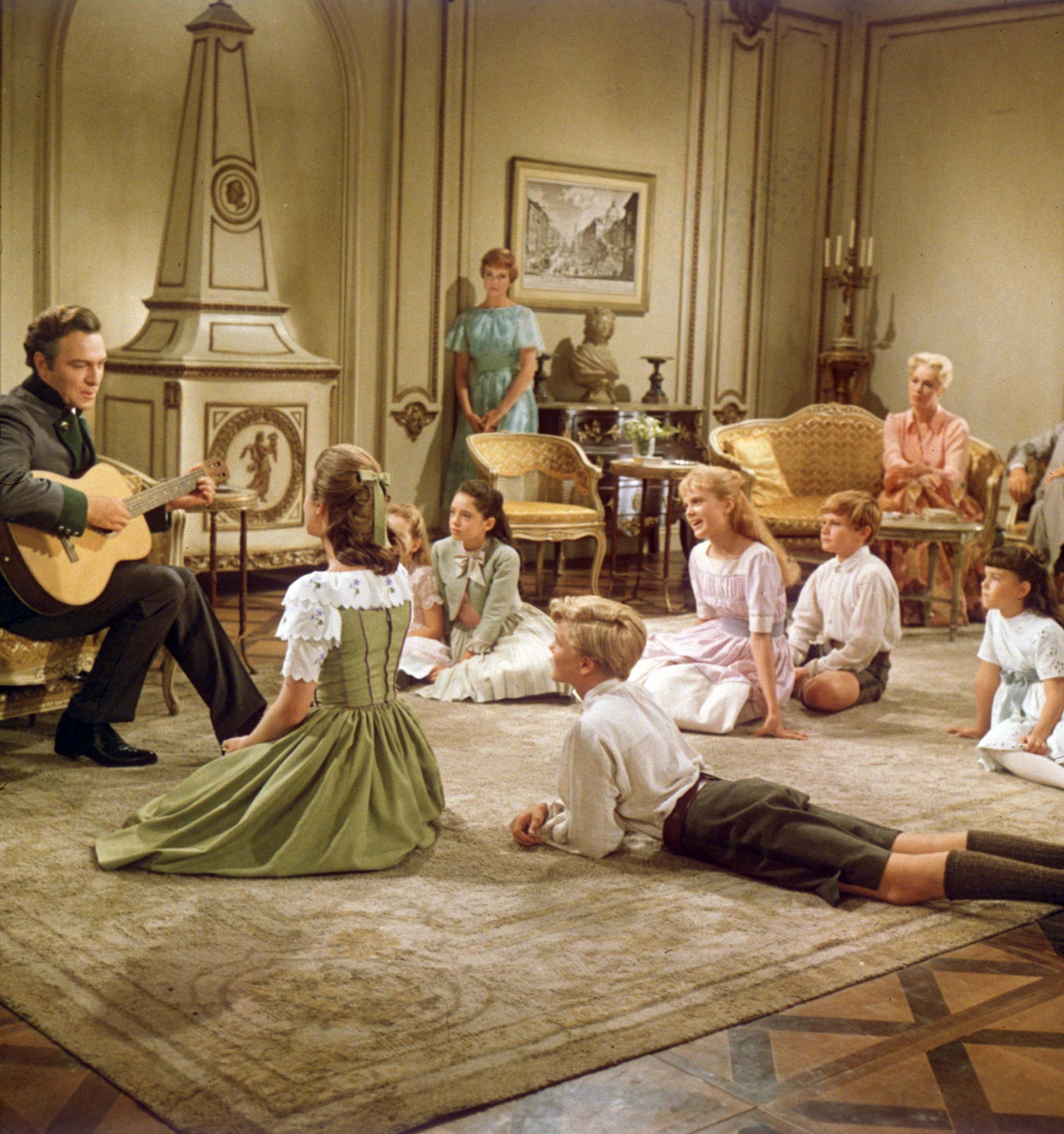

The von Trapp family had always been musical in nature. Before his first wife died, Captain von Trapp and his children made a habit of singing and playing musical instruments as a casual hobby. When a young novitiate named Maria Kuschera joined the household as a governess in 1926, she brought along her own talent and enthusiasm for music and, once she and the Captain married, the von Trapps’ love for music blossomed and grew. The children were taught four-part harmony and how to play instruments such as the viola da gamba, the recorder, and the spinet. Musical performance soon evolved into a pleasant after-dinner pastime for the family.

In 1938, Nazi party officials requested the von Trapps’ presence at a birthday celebration for Adolf Hitler, whose army had just marched into Austria.

The sound of the von Trapps’ music might have remained an endearing hobby were it not for a key player (literally!) who entered their villa and their lives in the mid-1930s. Father Franz Wasner was a local Catholic clergyman who came to the von Trapps to perform mass and was pleasantly astonished by their musical gifts; luckily, he was a trained musician and happily devoted himself to “upping their game.” Wasner’s devotion to the family—and his coaching skills—cannot be underestimated; he arranged their harmonic breakdowns and created sophisticated musical arrangements for their voices and instruments and expanded their somewhat limited repertory to include the very best of the liturgical and folk music canon. Wasner gave the von Trapps a professional technique and a professional sheen; a good thing too—they were about to become professionals.

The Salzburg Festival was Austria’s premier venue for singing artists and a famous soprano named Lotte Lehman promoted and prompted the von Trapp family into appearing there. Although initially hesitant to do so—patriarch Captain Georg took a dim view of the commercial spotlight—the family made their debut in 1937 and became an immediate sensation. The Salzburg Trapp Choir, as they were known professionally, enchanted audiences with a disarming combination of technical skill with a lack of pretension or artifice. Dressed in the folk costumes and traditional jackets of their native Austria, the Choir would provide a mixture of liturgical pieces arraigned by Wasner (Bach and Brahms, as well as 16th century composers such Orlando de Lassus and John Dowland) with folk songs known and beloved by Austrian audiences for centuries. There were no “original songs” created for their concerts. Audiences adored the Trapp Choir and soon there were concert invitations for venues across the region. One potential command performance would change their lives forever.

The slick and obstreperous dance arrangements of the late 1930s swing era had taken over commercial radio; audiences began to crave something simpler and more heartfelt.

In 1938, Nazi party officials requested the von Trapps’ presence at a birthday celebration for Adolf Hitler, whose army had just marched into Austria. That was one invitation the singing group preferred to decline. They knew their days under the Nazi regime were numbered but as fate—or talent—would have it, the von Trapps already had several invitations to perform outside of the country. They followed that particular byway and eventually made their way to New York City, where the whole clan—Maria, the Captain, seven children (plus one more on the way) and Father Wasner as well—landed commercial representation with the esteemed Columbia Artists Management.

America was a brave new world for the von Trapps and, in order to succeed here commercially, they had to meet their American audiences halfway. There was not an overwhelming embrace of German culture in America during the days and months prior to World War II, so the family’s management simplified their professional names; they were now the Trapp Family Singers. Further refinements meant recalibrating the “act” in performance. The family would perform their classical polyphonic pieces in the first part of the concert, then change costumes into their Austrian folk garb and sing more contemporary folk songs: Columbia Management insisted on their adding some English-language songs as well. Concerts in December would include “Away in a Manger” and “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen” and soon the Trapp Family Singers would land a much-coveted recording contract with RCA Victor. By the time World War II began, the Trapp Family Singers were an integral part of the commercial musical scene.

In addition to their undeniable talent, the Trapp Family Singers were lucky in that their American concert tours coincided with a new nationwide fascination with folk music and the ways that it broke down the wall between highbrow and popular culture in America. The slick and obstreperous dance arrangements of the late 1930s swing era had taken over commercial radio; audiences began to crave something simpler and more heartfelt. Singers accompanied only by their own acoustic instruments, such as Woody Guthrie on guitar or Pete Seeger on banjo, used an array of traditional songs from the heartland to capture urban audiences with a liberal bent up north, while a group like the Carter Family tapped into songs beloved on porches, campfires, and congregations down south.

American audiences also sympathized with the von Trapps as a group of refugees who had made something of their lives in their new country and celebrated their endangered culture by singing about it. Perhaps most indicative of their new status as Americans, they became, as Columbia Management had hoped, a commercial success. The Trapp Family Singers were Columbia’s most successful choral group, averaging more than a hundred concerts a year during the late 1940s and early ‘50s and averaging fees of $1000 per concert. By the time Maria “broke up the act” in 1955, the Trapp Singers had become an annual holiday fixture at one of New York’s premier concert venues, Town Hall, and recorded two successful Yuletide albums for Decca Records.

So, when producer Leland Hayward was contemplating the stage version of the von Trapps’ story for Broadway, he was dealing with a musical group that still had considerable currency with contemporary audiences. It was Hayward’s original intention to include the von Trapps’ repertoire of traditional musical selections, but he thought it could be augmented with some new Broadway material; he approached his old South Pacific colleagues Rodgers and Hammerstein. The songwriters liked the material but competing with Bach and Brahms was not their cup of tea. “[That idea] seemed to me most impractical,” said Rodgers in a New York Times interview. “Either you do it authentically—all actual Trapp music—or you get a complete new score for it.” So, a new score by Rodgers & Hammerstein would simply have to do.

To prepare, Rodgers attended a few concerts of Catholic liturgical music in New York City, but this was the closest Rodgers ever got to musicological research for the project; his pure intuitive musicianship usually made the songs sound effortlessly like one-part Tin Pan Alley and one-part Austrian folk songs. In fact, The Sound of Music contains some of his most effective pastiches; the “Preludium” that opens the stage show could easily fool all but the most sophisticated liturgical scholars and the “Laendler” folk dance that brings the Captain and Maria together for the first time, with its faint inversion of “The Lonely Goatherd,” sounds for all the world like a pure native Austrian tune. And, of course, the heartfelt simplicity of “Edelweiss” sounds so authentic that it has been mistaken, on more than one occasion, for the Austrian national anthem.

By the time The Sound of Music opened on Broadway in 1959 and the film version premiered six years later, the whole world knew who the Trapp Family Singers were. The music industry knew it too: RCA Victor re-released some original von Trapp recordings from 1939 as The Sound of Folk Music (from Many Lands) and the Trapp Family Singers—who had essentially disbanded in 1955—hastily reconstituted themselves in the studio to sing formal arrangements (by Father Wasner!) of the Rodgers & Hammerstein score to The Sound of Music on RCA Records. Talk about a musical round!

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.