The Enduring Relevance of Show Boat

SHOW BOAT is a musical play about reinvention, the irrepressible spirit of showbiz people, and what we make of the endless passage of time—time that flows on like a mighty river. On the surface, it might seem that this famed show is a love story, or a story about a family—maybe about a family and its servants and employees. Or, put more grandly, it might appear a story of Black and white life, music, and dance on the great and fraught canvas of American history. An adaptation of the epic novel by Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Edna Ferber, Show Boat has been interpreted at various moments and by various audiences as all of these and more.

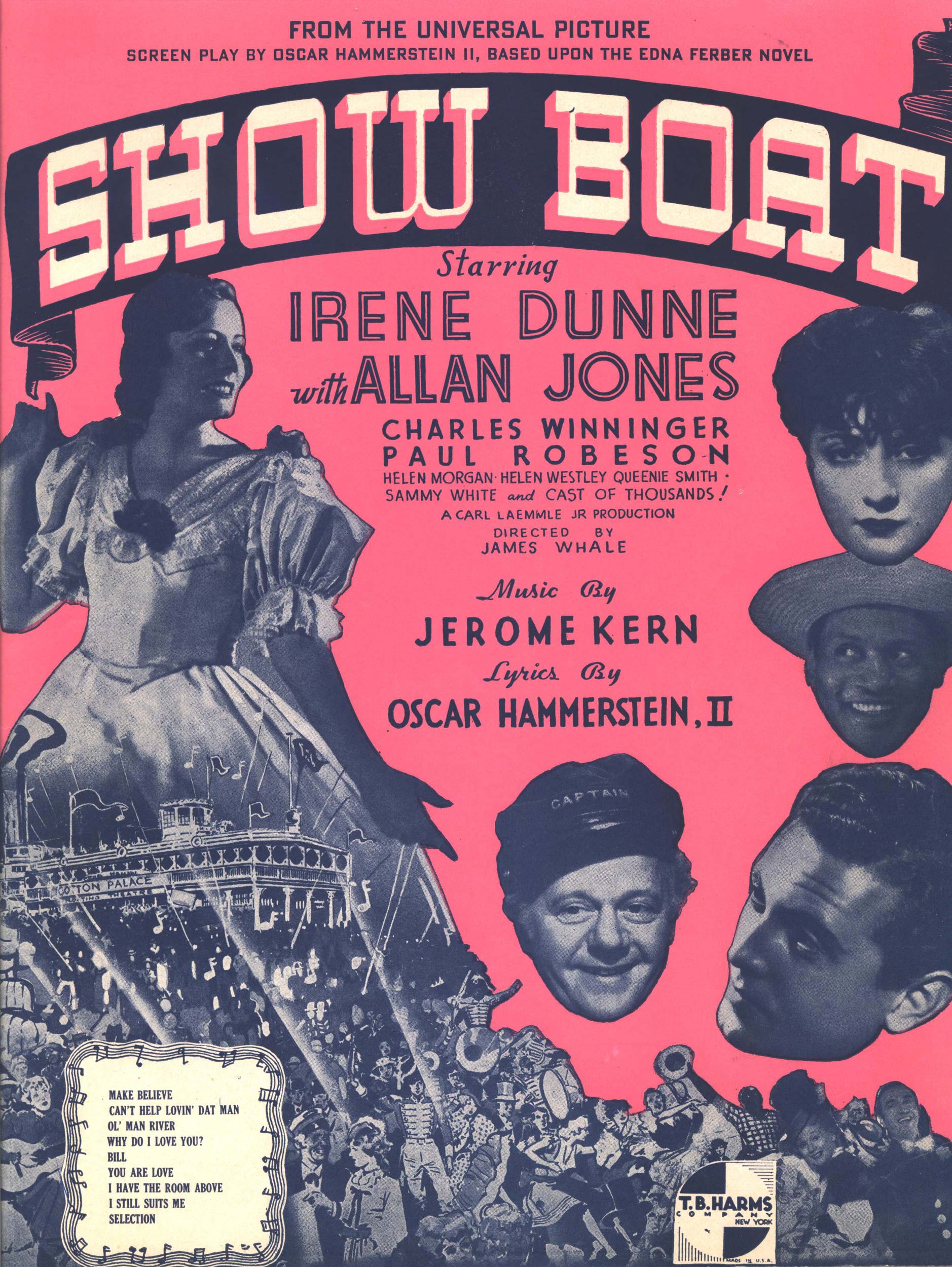

When it premiered on Broadway in December 1927, in a lavish production bankrolled by Florenz Ziegfeld that rivaled the opulence of his Follies, its authors were already accomplished creators for the musical stage and well versed in writing both operettas and musical comedies. Still, in creating Show Boat librettist Oscar Hammerstein II and composer Jerome Kern were, like any artists with the resources and desire to craft a musical, simply trying to work out the best way to tell a particular story in music from their own perspectives, the conventions and vogues of their era, and the specific talents of the performers they sought to showcase. The result is a work that has been beloved and reviled, celebrated and revised, venerated and reimagined over the past century. In these ways, Show Boat’s journey through theatrical history is also a tale of reinvention, the irrepressible contributions of showbiz people, and time that flows on like a mighty river.

Although today the process of developing a new Broadway musical can take the better part of a decade, Show Boat was written in just over one year. Hammerstein was 31 years old when Kern, a decade older, invited him to begin working on an adaptation of Ferber’s bestselling novel in the fall of 1926. To reprise the phrase an admiring Stephen Sondheim once used to pay tribute to him, Jerome Kern remains one of the great melodists of the American musical theatre. He painstakingly constructed his melodic lines note by careful note, until they took to the air with tuneful but unexpected twists and turns and unsuspected harmonic arrivals.

Hammerstein brought to the collaboration his finesse in writing lyrics for a wide range of characters, whether lovers aspiring to romantic union in high-flying operettas or vaudeville stars lightly tapping their troubles away. Many songwriters of the day were simply after the next hit song, writing numbers that were easily interchangeable from one show to the next. But with Kern, Hammerstein–also the de facto director of the original Show Boat–took his versatility as a lyricist further and began to write deeply from the perspectives of individual characters with their hopes, regrets and longings. As best he could, Hammerstein worked to humanize each character and create opportunities for people in musicals to sing in specific but everyday language that flowed from the way he understood their class, race, and regional backgrounds.

Although today the process of developing a new Broadway musical can take the better part of a decade, Show Boat was written in just over one year.

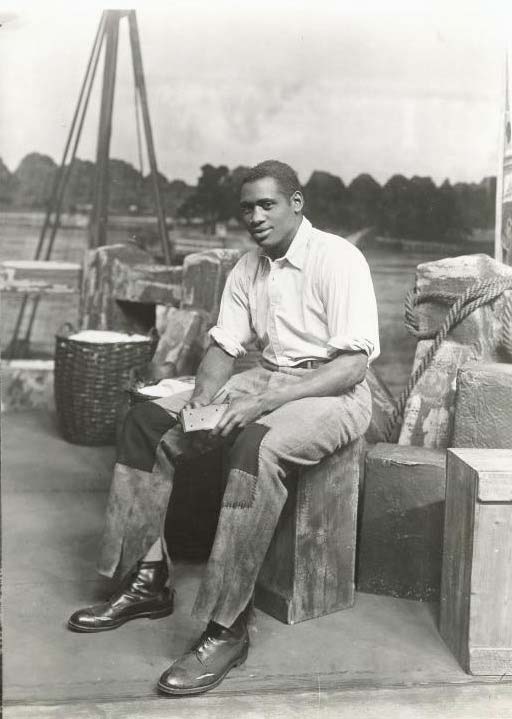

Paul Robeson’s Voice and the African American Spiritual

Alongside white theatre professionals Kern, Hammerstein and Ziegfeld, the acclaimed African American bass-baritone Paul Robeson must also be recognized for his profound impact on the writing of the show. It was Robeson who inspired the song that is itself the show’s greatest star: “Ol’ Man River.” True, he declined to appear in the original Broadway production and was only persuaded to accept the starring (though supporting) role once it was clear Show Boat was a hit; the role of the stevedore Joe who leads the Black ensemble and offers up pensive folk wisdom on the banks of the Mississippi River was first played by the Black operatic baritone Jules Bledsoe. However, Hammerstein and Kern conceived the framework for the entire show as an opportunity to showcase Robeson’s powerful vocal talents and stage presence, which at the time had New Yorkers enthralled.

1920s New York was a city gone mad for jazz rhythms, when white fascination for Black culture led many to brave the trip uptown to the blue dazzle of a Harlem Renaissance nightclub. At the same time, the stirring sound of spirituals forged in the fire of enslaved life offered another form of Black music that white audiences thrilled to, and one that Black audiences felt advanced the cause of racial justice. Concert performances of African American spirituals were quite the thing, sung by a dignified soloist accompanied by piano. A ruggedly handsome lawyer and athlete as well as a serious actor, Robeson more than fit the bill. One of the earliest drafts of Show Boat even made space for him to recreate the kind of recital he was famous for, with a mini-concert of spirituals right in the middle of Act 2. Much had to be revised when Ziegfeld’s efforts to sign Robeson proved futile, but the vivid musical material written for his voice remained. And Robeson was not the only performer to impact the direction Show Boat would take.

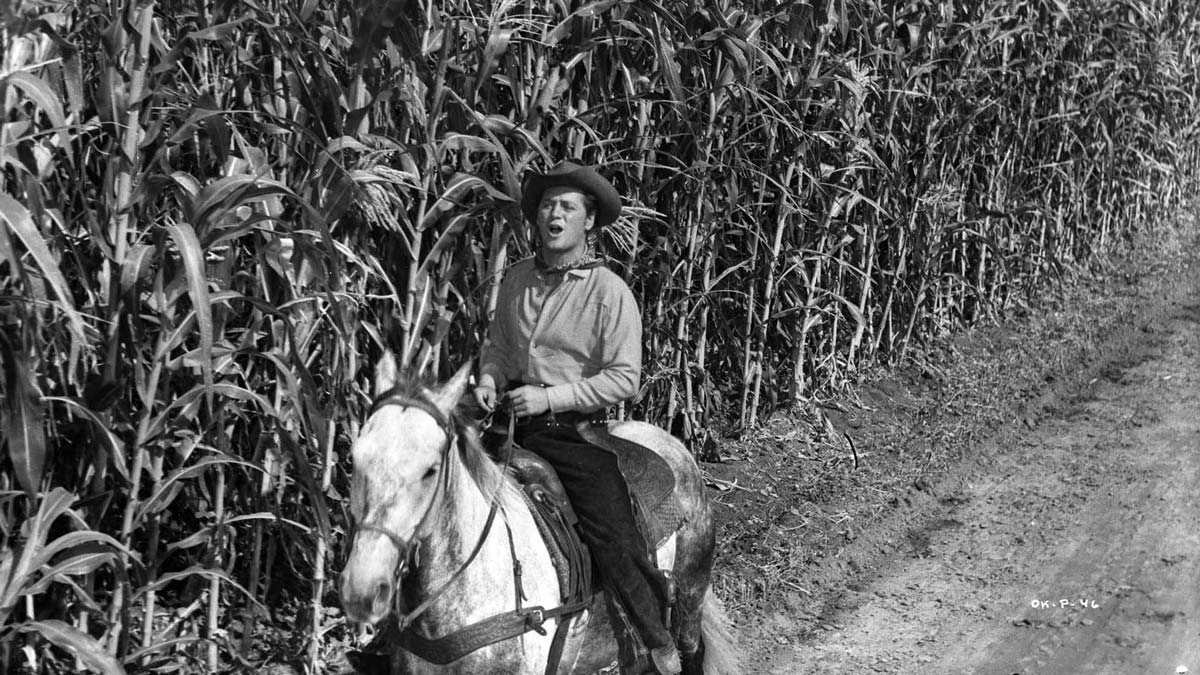

In Hammerstein and Kern’s musical, the troupe that travels the Mississippi River from 1887 to 1927 on the floating theatre the Cotton Blossom prove a colorful lot. There is the ever-practical but henpecked impresario Captain Andy trying to drum up ticket buyers, his dour and self-righteous wife Parthy finding new ways to misplace her love, and their daughter Magnolia who transforms over the show’s 40+ year timeline from a naïve and stagestruck girl to an understudy who gets her big break, to a starry-eyed bride, to a courageous single mother going back into showbiz to provide for her child. The cause of all that transformation is one Gaylord Ravenal, a sweet-talking Southern gentleman with a winsome smile and an unfortunate gambling addiction. Then there is vivacious Ellie, one half of the troupe’s song-and-dance team, and Frank, her underappreciated but cheerful partner. The dependable Joe and his wife Queenie, the ship’s cook. Steve, the boat’s leading man, who professes ardent love for his scene partner both onstage and off. And finally, Magnolia’s girl crush—Julie, leading lady of the floating melodrama, harboring a dark secret and destined for tragedy in the larger melodrama of American racial life.

1920s New York was a city gone mad for jazz rhythms, when white fascination for Black culture led many to brave the trip uptown to the blue dazzle of a Harlem Renaissance nightclub. At the same time, the stirring sound of spirituals forged in the fire of enslaved life offered another form of Black music that white audiences thrilled to, and one that Black audiences felt advanced the cause of racial justice.

Helen Morgan’s Voice and the Tragic Torch Song

The star who first played the white-passing Black singer Julie was Irish American torch singer Helen Morgan. Now a faded historical figure, Morgan was famous in late 1920s America for her tremulous vocal pathos and sad little songs, as well as frequent run-ins with the law around the sale of alcohol in the contentious days of Prohibition. Like Robeson, Morgan significantly inspired Show Boat’s authors. Of course, the song Julie first sings to Magnolia, “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” was written early and not for Morgan per se. (Singers today often soften the dialect lyrics typical of Hammerstein’s time, i.e., restoring “dat man” to “that man.”) But, sung by Magnolia, the song returns in Act 2 in a pivotal scene built around Morgan’s gifts. It is 1904 and the onetime show boat star, down on her luck and deep in her drink, rehearses her new number “Bill” at the Trocadero club in Chicago. Then, overhearing Magnolia audition with the tune she taught her years ago, Julie quietly sacrifices her job to create a chance for the younger singer.

Held in Morgan’s voice and a storyline about a woman consigned to yearn for impossible love, the wistful “Bill”—an outtake from an early Kern show with lyrics by P.G. Wodehouse that Hammerstein retrofitted to new ends—was deeply affecting. Like “Can’t Help,” it is a song about being desperate for the wrong sort of man. This was Morgan’s specialty: languishing against or atop a piano to sing about longing. The tabloid-ready singer got her start in Chicago speakeasies and always knew where to find a stiff drink in Prohibition-era New York. For her, Hammerstein made Julie a singer of tear-stained torch songs who can only slip quietly into the night on another forlorn drinking spree. In this way, Show Boat restages the trope of the tragic mixed-race woman, as Julie can never achieve any lasting happiness in the show. This racial stereotype of 19th- and early 20th-century popular culture resurfaces every time Show Boat returns to the stage. But when Morgan played Julie, this important supporting role also compelled audiences to sympathize with the character’s plight as echoed in the real life of a white torch singer who takes refuge in a flask and a sad song. Only much later was the role played by fair-skinned Black women—notably the West End’s Cleo Laine in 1971 and Broadway’s Lonette McKee in 1983 and 1994.

Show Boat’s Racially Charged History

Show Boat remains enduringly relevant and enduringly problematic because of its racially charged themes and history. Certainly, Hammerstein and Kern were well-intentioned in their efforts to create meaningful material for a Black singer-actor and to welcome a Black ensemble onto the same stage where a white ensemble performed in the same show—a move with very little theatrical precedent. Ziegfeld was also known to support Black artists; as early as 1910 he defied strong opposition to hire leading Black performer Bert Williams as a headliner for the Ziegfeld Follies. But it was explicitly written into Williams’s contract that he would not be onstage at the same time as the white chorus girls, a concession to racist fears that Black men were destined to predatory behavior from which white women must be protected. With Show Boat, too, the gains for racial equity were tarnished by limiting beliefs that disempowered and disparaged Black people, and from today’s perspective it can seem the bar was set far too low.

In 1927, the very first thing audiences saw when Show Boat’s curtain rose was a Black chorus launching a show with an interracial cast—a sign of progress toward equitable race relations. But the first word this ensemble sang was a racial slur, referring to Black people in derogatory terms and their hard labor on the river. African American audiences, critics, and performers voiced criticism about this language from the start and for decades after. In the original production, some Black chorus members resisted by not singing at all on the notes attached to the offensive word. We can celebrate how in later productions this lyric was changed, often to “Here we all work on the Mississippi” (instead of “N—rs all work on de Mississippi…”) but this seems a very small, sad thing to have to celebrate. We may applaud the magnificent solos enshrined in the Broadway canon for Black actors like Robeson to sing as Joe, but it is extremely difficult to square that applause with knowledge that Joe’s wife Queenie was originally played in blackface by Italian-American performer Tess Gardella, listed in the playbill by the distasteful name of her vaudeville persona “Aunt Jemima.” And we can celebrate that this role was subsequently played by Black women, first by blues singer Alberta Hunter in London in 1928, and with Tony Award-winning regal grace by Gretha Boston in the 1994 hit Broadway revival. But these often feel like celebrations with built-in compromises, and the fraught history of Show Boat’s racialized language and casting lingers.

Show Boat’s African-Inspired Dance

One area that is often overlooked in histories of Show Boat, especially because of how decisively it has been taken up by American opera companies in recent decades, is its rich scope for dance. The musical has been reimagined in different ways and at different times to showcase an array of Black dancers and dance forms. The prominence and then disappearance of African-inspired dance in the show traces one strand in the long history of Show Boat productions working to revise racial stereotypes in a bid to keep the show stageworthy.

The key dance scene is the Act 2 opener set at the 1893 World’s Fair. At its close, the white chorus, playing fairgoers, encounters the Black chorus, playing scantily clad citizens of the African nation of Dahomey. Such anthropological exhibits of “authentic primitive natives” were main attractions at world’s fairs in this age of European imperialism. Appalling from today’s perspective, the premise was that non-white people would be put on display for scrutiny by a whites-only audience. But the extended song and dance “In Dahomey” as originally staged in Show Boat included some surprises. First, the Black chorus effectively chased the white chorus from the stage: the whites fled in fear, a security breach no actual world’s fair would have tolerated but a necessity on Broadway to give the stage over to the Black cast. Second, after singing supposed African chants, the Black chorus dropped the pose and burst out in one of the score’s jazziest choruses. Hammerstein’s lyric revealed these “Dahomey natives” to be just another bunch of showbiz folks: Black New Yorkers from Avenue A—Hammerstein knew Manhattan real estate history, and Harlem wasn’t yet the city’s Black neighborhood in the 1890s—hired to play a racial type. With this dance scene showcasing 1920s Black performers playing the racial type of 1890s Black performers playing the racial type of exotic “Africans,” Show Boat became perhaps the earliest meta-musical.

Later productions had to grapple with the question: What to do with “In Dahomey”? It’s a big number and, like so many of the Black ensemble’s numbers in the original Show Boat, it closed a big scene. In the 1946 revival produced by Rodgers & Hammerstein, the ironic jazz finale lyric was cut, four dance-only Black characters were added to the cast, and a new star of “In Dahomey” was created when the Trinidad-born dancer Pearl Primus was hired as the Dahomey Queen. (This was a figure not unlike that played by Viola Davis in the 2022 film The Woman King.) Primus, a self-choreographing concert dancer, built her dances on anthropological research and an emerging Black modern dance aesthetic later innovated by figures such as Alvin Ailey—who also spent some time in Show Boat revivals in the 1950s. Partnered by the Black male dancer LaVerne French, Primus also had a feature in Act 1. Reviewers loved her work and saw the inclusion of serious Black concert dance as a welcome and standout addition to Show Boat. French took over as the Dahomey King when the revival toured nationally and in review after review his dancing and that of the entire Black chorus was celebrated as the highlight of the production. Indeed, into the 1960s Black modern dance referencing African dance–often featuring athletic and powerful Black men–was a central part of Show Boat.

Then, from the 1970s forward, the entire Dahomey sequence disappeared. Perhaps the expense of staging the extravagant Act 2 opener at the world’s fair prompted the change. Perhaps the expense of a Black dancing as well as singing chorus also contributed—and an excellent chorus of Black singers was, of course, essential for effective delivery of “Ol’ Man River.” In retrospect, later productions of Show Boat reveal that its capacity to feature a range of Black theatrical types has dwindled, in effect making the world of the show whiter and boxing the Black cast into mostly stoic and serious spiritual-singing scenes.

How Will “Ol’ Man River” Keep Rolling Along?

For all its theatrical power, in the end Show Boat has endured for its array of song hits, with two for the Black cast foremost among them. Indeed, the nearly ritualized singing of “Ol’ Man River” is the standout moment in any production, often garnering a scattered standing ovation a mere twenty minutes into Act 1. Hammerstein and Kern knew how effective the song could be: unlike any other Broadway tune, “Ol’ Man River” is reprised three times in the course of Show Boat.The sight and sound of a Black man powerfully singing “Ol’ Man River” continues to elicit a profound reaction from white audiences. And Robeson, who sang the song for decades, recognized what it could do, even as he revised the lyric to give the lie to any notion of Black passivity in the face of suffering. For his own concerts, Robeson was known to adjust a few key words, shifting the focus from singing about resigned weariness to voice a commitment to fighting for justice for racialized and working-class people.

Some listeners may think the song is, in fact, an actual African American spiritual, and Kern’s stately, spare music rings true to the kind of song that inspired its contours. But the fact remains that the striking vocal music created by enslaved Black people often held coded messages with vital information to help people find their way to freedom. The spiritual “Deep River,” for example, with its themes of crossing over the River Jordan to the Promised Land held out the very real hope for a better life in a new place. While “Ol’ Man River” may not yet seem to reach for this promise or commitment to justice, it nonetheless has the power to call up the depth of emotion that many spirituals carry. Today, it is up to the next generation of musical theatre artists and audiences to ask ourselves: What is it that we as showbiz people and show tune fans will labor and fight for now…as time, like a mighty river, keeps rolling along?

Masi Asare is a songwriter, dramatist and Northwestern University professor whose work includes Paradise Square (Tony nomination), Monsoon Wedding, and the forthcoming book Voicing the Possible: Technique, Vocal Sound, and Black Women on the Musical Stage.

Todd Decker is the Paul Tietjens Professor of Music at Washington University in St. Louis and the author of Show Boat: Performing Race in an American Musical and Who Should Sing "Ol' Man River"?: The Lives of an American Song.