OUT OF MY DREAMS: The Psychological Canvas of Choreographer Agnes de Mille

If she had done nothing else other than create the “Dream Ballet” that concludes Act 1 of Oklahoma!, choreographer Agnes de Mille would have contributed a great leap forward in the American musical.

As it happens, de Mille created far more than that – including collaborating extensively on the premieres of the first three Rodgers & Hammerstein musicals – and became, seemingly overnight, the most indispensible choreographer of the post-war era. It wasn’t always easy and it certainly wasn’t inevitable, but the petite, determined, often querulous, perennially anxious Agnes de Mille changed the face – and the arms and the torso and the legs and the feet – of musical narrative on Broadway. She was, to use the phrase that suits her best (and deployed by Ted Chapin, CCO of The Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization), formidable.

De Mille was born in 1905 into a distinguished and complicated artistic family; her father was a successful playwright, and her uncle, Cecil B. de Mille, was a Hollywood pioneer and one of its most legendary directors. As a girl, she was shuttled between two stimulating environments – her family’s artistic retreat in upstate New York and the film colony of Hollywood – and soon developed a passion for performance, first as an actress, then as a dancer. Her career choice was frowned on by her imperious father, which only exacerbated de Mille’s intense desire to please him. Her mother smiled more kindly on her ambitions and sponsored an endless series of ballet lessons and recitals for Agnes in both America and England. It soon became apparent that Agnes’s talent lay more in choreography than in performing – she never had the ideal ballerina figure – and, by the early 1930s, she was choreographing dances for musical comedies in the West End and on Broadway as well as a brief and disastrous sojourn in Hollywood doing dances for a film directed by her uncle.

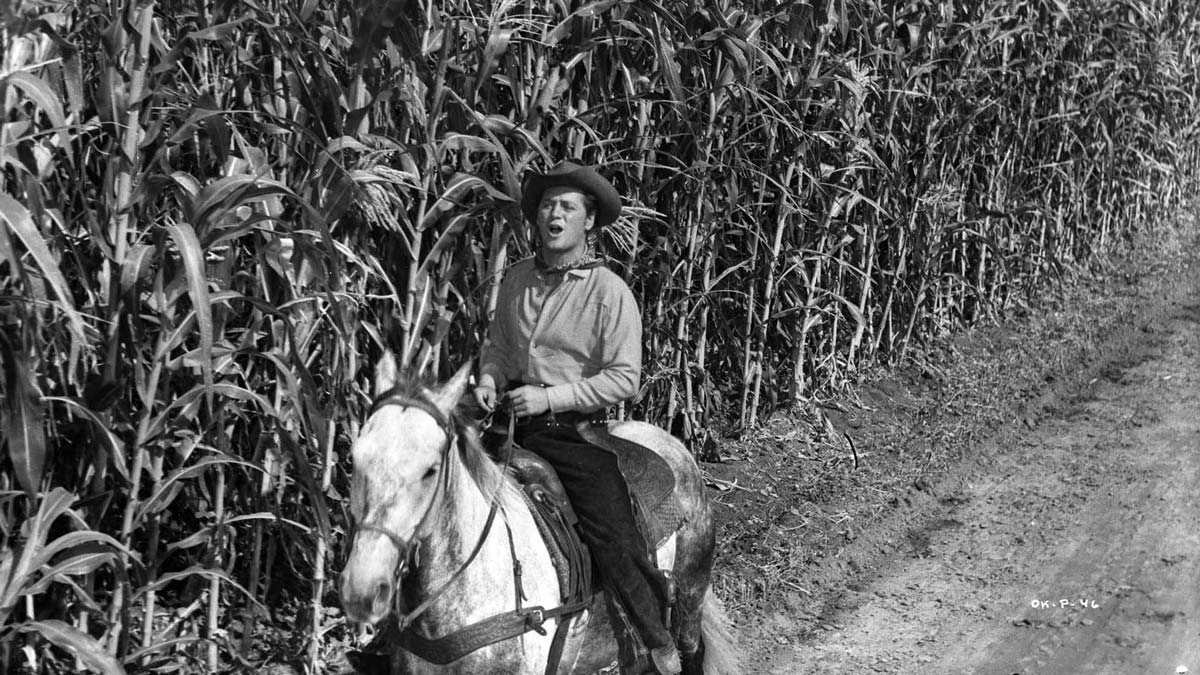

In October 1942, de Mille staged a piece of her own for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo at the Metropolitan Opera House. Rodeo, with music by Aaron Copland, was pure folk Americana – a popular trend in the war years – about a cowgirl, danced by de Mille herself, whose unbridled independence incites the dueling passions of two champion riders. The fresh, passionate athleticism of the ballet created a sensation. Rodeo was the perfect audition piece for Oklahoma! – it would be like auditioning for Damn Yankees a week after winning the World Series. Richard Rodgers professed some initial uncertainty, thinking de Mille’s background was too classical – perhaps because he himself hadn’t realized the depth of his new project – but five months after Rodeo, de Mille plunged right into the creative development of the show. Without a shred of deference to her collaborators, she defied director Rouben Mamoulian by casting strong, idiosyncratic dancers for her corps, rather than a chorus line of gooey glamour girls.

Although she would not be the last choreographer to give their chorus dancers specific characters and individualized personas (Jerome Robbins would refine that art in the 1950s), de Mille fused her early acting ambitions with her skill as a choreographer. Each of her dancers in Oklahoma! had a meaningful relationship to the community and to each other; later on in Carousel, in a more stratified setting, she also added the important shading of social caste to the context of her dancing chorus. For de Mille, gesture and presence had to have a purpose on stage, even more importantly, a purpose that told the musical’s larger story with clarity and objective. “Otherwise,” she once demonstrated by tossing her hands arbitrarily in the air, ”you might be as well be throwing open the window.”

“The petite, determined, often querulous, perennially anxious Agnes de Mille changed the face – and the arms and the torso and the legs and the feet – of musical narrative on Broadway.”

Her insightful way of crafting narrative through bodies-in-motion reached its apotheosis in the dream ballet that concludes Oklahoma!’s Act One, known as “Laurey Makes Up Her Mind.” The focus was to be on Laurey, the leading character, as she contemplates choosing either Curly or Jud to escort her to the box social. Oscar Hammerstein initially proposed a ballet with a circus theme that would be, in his words, “bizarre, imaginative and amusing, never heavy,” but de Mille was of another opinion:

I said [to Hammerstein], this is the kind of dream that young girls who are worried have. She’s frantic because she doesn’t know which boy to go to the box social with. And so, if she had a dream, it would be a dream of terror, a childish dream, a haunted dream. Also, you haven’t any sex in the first act. He said, haven’t I? I said, goodness, no. All nice girls are fascinated by [the darker side of sexuality]. Mr. Hammerstein, if you don’t know that, you don’t know about your own daughters.

In de Mille’s more complex scenario, Laurey imagines herself on her way to her wedding with Curly, only to be abducted by Jud and brought to his Expressionist den of iniquity full of dance-hall girls, inspired by the dirty French postcards that adorn his bunkhouse. (De Mille was emphatic that the audience should not be watching a real house of ill-repute, but rather the kind of place that the virginal Laurey imagines it to look like.) Laurey is repelled by Jud’s unapologetic earthiness, but also strangely drawn to him; when he “kills” Curly and carries her away, her worst fears – if, indeed, they are her worst fears – are realized. The genius touch in the piece is that at the very end of the act, Laurey, awakened from her dream/nightmare, confronts the real-life Jud, who escorts her to the social. It is as if the anxieties of the dream have not simply reflected reality, but conjured it up. It is pure Freud – transported to the Great Plains.

De Mille herself had already been in psychoanalysis, trying to resolve her own conflict between two very different men in her life – but on-stage such psychological conflict is served up in a tasteful and accessible manner. More to the point, the Dream Ballet brought the expressive possibilities of dance in the musical to a new narrative level. There had, in fact, been dream ballets in musicals prior to Oklahoma! but, as in Pal Joey, where the leading character declares he wants to own a big nightclub and then – whammo! – the chorus is ushered on to show us a dream version of the big nightclub, these earlier ballets only told the audience what it already knew. In de Mille’s groundbreaking vision, the characters are revealing not only something the audience doesn’t already know, but something the characters don’t even know about themselves.

The success of Oklahoma! in 1943 made de Mille the preeminent choreographer of Broadway. Over the next two years, she had three other major shows: Kurt Weill and Ogden Nash’s One Touch of Venus, Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg’s Bloomer Girl, and Carousel, which reunited her with her Oklahoma! collaborators. Each of these shows allowed de Mille to demonstrate her narrative skills in various ballets. Set in the North during the Civil War, Bloomer Girl had a particularly evocative ballet that portrayed women awaiting the return of their menfolk from the battlefield; some of the creative staff found it too dark, but de Mille stuck to her guns, the collaborators stuck with de Mille, and it became the dramatic highlight of the show.

De Mille herself had already been in psychoanalysis, trying to resolve her own conflict between two very different men in her life – but on-stage such psychological conflict is served up in a tasteful and accessible manner.

In Carousel, her pièce de résistance was a twelve-minute ballet (cut down from an hour in rehearsals) that told the story of Louise, the adolescent daughter of Julie Jordan and Billy Bigelow, a character whose development and personality were expressed almost entirely through dance. The ballet expressed the girl’s loneliness as an outsider; her tomboyishness; her ostracism from the snobbish community because of her father’s past; and her wistful, near-Freudian, infatuation with the father she never knew. The latter section was made even more heartbreaking because Louise dances with a touring carnival roustabout (if, in fact, it is a dance and not a vision of her imagination) who resonates as an idealized Billy Bigelow but who, in the end, sees her only as a child and a “pal” – not as a romantic equal. What would have taken painful pages of exposition in a conventional narrative was rendered by de Mille in a manner that made strong men weep.

All of de Mille’s major Broadway ballets of the 1940s centered around women, women in various stages of romance, courtship, marriage and – ultimately – disappointment. When discussing the narratives of these ballets, and the situations of the women at the center of them, de Mille frequently used words such as “rejection,” “fear,” “abandonment,” and “isolation.” She came by these feelings the hard way. Mary Rodgers, the daughter of the composer and a friend of de Mille’s said, “People were always leaving Agnes: Her father left her; in the 1940s, her husband, Walter Prude, was off in the Army. She never felt like a very attractive young woman, there’s a degree of pathos in anything Agnes does that has to do with saying good- bye. She was very empathetic about that – she felt those things very acutely – and it shows up in everything she does.”

In addition to de Mille’s powerful emotional empathy, she had a deeply ingrained sense of time and place, particularly as it revealed social class distinctions. Perhaps because she grew up in such an elite circle of over-achievers, de Mille knew the difference between how “good girls” and “bad girls” behaved; how women were perceived in polite society; and the full array of carefully granulated manners between men and women, between upper and lower classes. No choreographer – and few directors, for that matter – had such an exquisite sense of 19th-century etiquette.

That may be why de Mille was less successful on her third effort for Rodgers & Hammerstein, Allegro (1947), which was mostly set in contemporary times. She also took on the role of director-choreographer, one of the first individuals do so in Broadway history. Unfortunately, the show’s complex dramaturgy and the logistical nightmare of running rehearsals confounded her, and Hammerstein had to intervene, directing the book scenes. By the time the 1940s concluded, other choreographers with other styles would go on to make their own imprints on the Broadway musical: Jerome Robbins in the 1950s; Bob Fosse and Gower Champion in the 1960s; Michael Bennett in the 1970s.

But while they were following in de Mille’s footsteps – sometimes quite literally – de Mille herself would continue to choreograph ballets for both the musical and classical dance stage for another quarter of a century, as well as direct the occasional show. She worked with one of her greatest dancers, Gemze de Lappe, to memorialize much of her choreography for posterity. She was relentless in her quest to gain respect for her craft within the Broadway community, lobbying for better-paying contracts for dancers and residual payments for choreographers. Ironically perhaps, her style of choreography – particularly the dream ballet – was copied and diluted by so many diverse hands over the years that her own original work lost some of its seminal impact.

Still, Agnes de Mille remains the choreographer and visionary who brought Rodgers & Hammerstein’s initial work to life, creating astonishing successes out of unpredictable material; she reached into the depths of her own dreams, brought them out into the kinetic bodies of graceful and robust dancers, and, in so doing, inspired the dreams of countless audiences.

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.