WE KNOW WE BELONG TO THE LAND: The Territory of Oklahoma!

Oscar Hammerstein II was always a clever and engaged fellow, the kind of fellow, you suspect, who grew up reading the daily newspaper even as a kid. Is it possible, then, that on November 10, 1907, as a twelve-year-old, he read the full-page New York Times article: “And Now Oklahoma – the Forty-Sixth State”? Might the young Hammerstein have been fascinated by a brand-new state?

Thirty-six years later, a musical that concluded with an ode to Oklahoma’s incipient statehood fascinated Broadway – and, eventually, most of America. For a significant part of that audience in 1943, the journey of Oklahoma from territory to state was certainly within living memory, not lodged in the deep and dusty recesses of the history books (although Hammerstein’s collaborator, Richard Rodgers, was only five when it occurred). That audience would have also been conversant – and comfortable – with the values and imperatives of westward expansion as expressed at the time. Although Oklahoma!, as a piece of musical theater, is largely animated by the romantic trials and tribulations of its two leading couples, its thematic spine, like that of its source material, Green Grow the Lilacs (written by Lynn Riggs, who was born and raised in Oklahoma), is the desire to expand, to live on one’s own land, and belong to it, too.

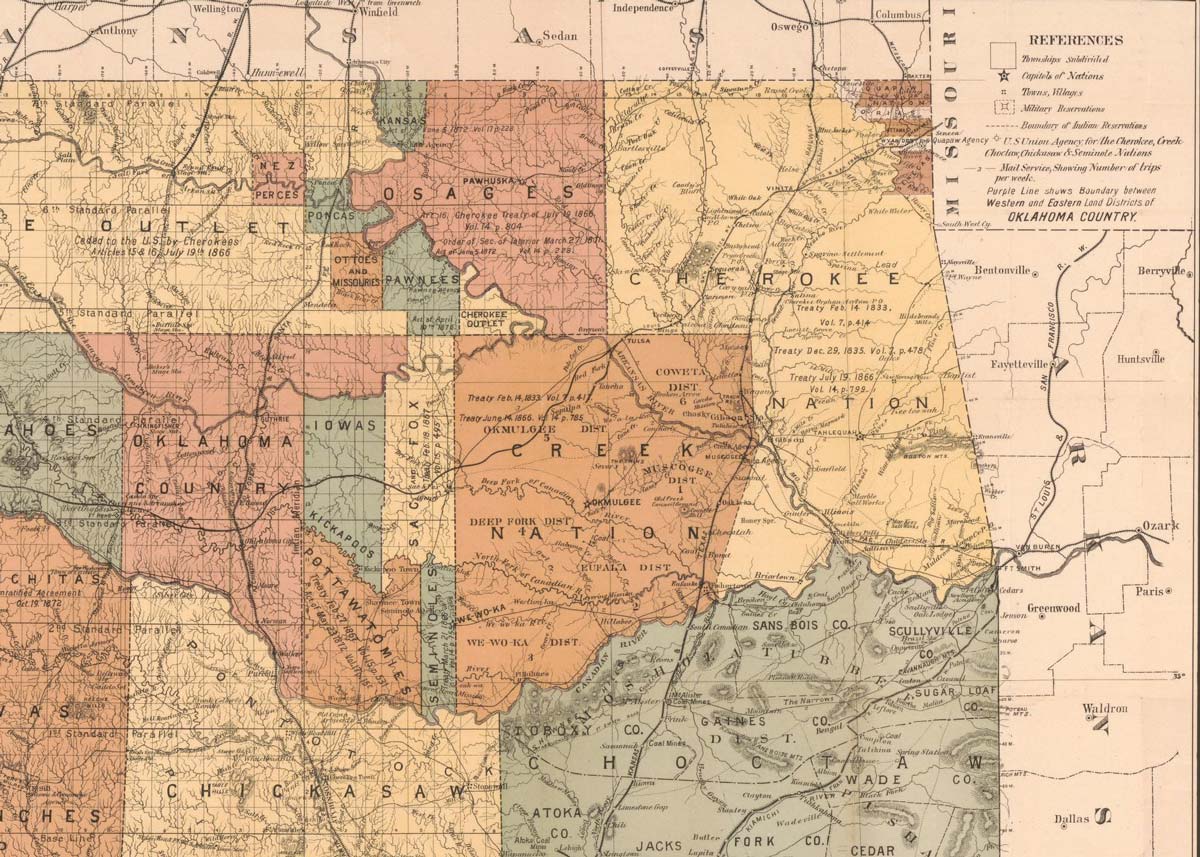

Oklahoma itself – located pretty much smack-dab in the middle of the Northern American continent – became part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. It was inhabited, back then, by nearly a dozen Indigenous tribes, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Osage and Seminole Nations. In the middle of the 19th century, these tribal nations – along with other Native Americans – endured a painful and systematic relocation to the eastern part of Oklahoma along the Arkansas and Missouri borders by the U.S. government as part of The Indian Removal Act. After the Civil War, the natural attraction of Oklahoma’s bountiful resources – recently made available to non-Native Americans through the government’s relocation policies – proved powerfully attractive to settlers who saw the vast appeal of migrating westward.

When, in his lyrics, Hammerstein writes of “…barley,

Carrots and pertaters–

Pasture for the cattle–

Spinach and termayters!

Flowers on the prairie when the June bugs zoom–

Plen’y of air and plen’y of room–”

he might well have been drafting a rallying cry for those 19th-century settlers from the east. As an article from the Oklahoma Historical Society put it, “The agents of expansion, consequently, usually found in Oklahoma what they were looking for – exploitable natural resources, commercial opportunities, an agricultural paradise, a Great American Desert, a resettlement zone, and a military and administrative problem.”

Oklahoma itself – located pretty much smack-dab in the middle of the Northern American continent – became part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Indeed, woven within the utopian tapestry of Oklahoma as paradise were the strands of significant conflict. For much of the 19th century, before efficient railway transport, the land was used as a much-needed trailway for cattle drives from west to east. Cowmen (known more familiarly as “cowboys,” right?) were in charge of moving the cattle, and that made them both an essential part of the Oklahoman ecosystem. The cowmen’s horses weren’t just animals or conveyances for them; they were partners. “He rides for days on end/ With just a pony for a friend,” goes one lyric in “The Farmer and the Cowman,” and Curly’s painful decision to barter his “well broke” horse, Dun, toward the end of Act 2 demonstrates his deep affection for Laurey (and for Dun, too!).

Although cattle drives were a big (and necessary) business, it set up a deep-rooted rivalry between the cowmen and the farmers whose pastures were in danger of being decimated by the thundering herds. These two warring factions continued to spar into the early 20th century, as Hammerstein commemorated it at the beginning of the second act:

CARNES:

I’d like to say a word fer the farmer…

He come out west and made a lot of changes.

WILL (scornfully singing):

He come out west and built a lot of fences!

CURLY:

And built ’em right acrost our cattle ranges!

CORD ELAM (a cowman, spoken): Whyn’t those dirtscratchers stay in Missouri where they belong?

By the late 1880s, there were tens of thousands of “dirtscratchers” flooding into Oklahoma. The government relocation of the Native tribes to the east had already made room for these settlers in the central and western part of the territory. This program for expansion was formalized in a massive “Land Run” in the spring of 1889, when nearly 3,000 square miles of “Unassigned Lands” were opened for settlers to declare parcels for homesteading; if a family of settlers could stay on those parcels for five years and improve it, they would be permitted to own that land, free and clear. It’s no wonder Laurey and Aunt Eller work so hard to keep their farm going – and it demonstrates how much they rely on the impressive ranching skills of their farmhand, Jud, no matter how ornery he may be.

Within a few years, the pace of the new homesteaders grew to 50,000 people, necessitating an official division of Oklahoma into two parts: Oklahoma Territory, to the west, which held most of the new settlers, and Indian Territory, the northeastern part of the state, where the tribal nations had been relocated. These new homesteaders were not exclusively white; because much of the state borders Kansas to the north, a large number of Black settlers made the exodus southward in the years between the end of the Civil War and the Land Run of 1889. These “Freedmen,” as they were known, received parcels of land as well, understandably settling in close proximity to each other; as a result, scholars believe there were over 50 all-African American towns in Oklahoma. It is estimated that African Americans owned more than 1.5 million acres in both territories. As the Oklahoma Historical Society put it, “the significance [of black settlers in Oklahoma] resides in the determination of black people to escape discrimination, to seek reinforcement for their racial ideas, and to acquire some control over their own lives.”

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, self-sufficient and prosperous Black communities rooted themselves in the Oklahoma soil; paradoxically, their comparative successes only led to more deeply segregated towns. The imposition of Jim Crow laws and the tensions between Black and white communities reached a tragic climax in late May of 1921 when the Tulsa race massacre erupted within the accomplished Black district of Greenwood. Racist white interlopers invaded the district on a vengeful mission of death and destruction. The city of Tulsa was primed for this kind of raw explosion; it had burgeoned nearly overnight from an outpost into a major city as late as 1902, when oil was discovered nearby; it’s not even referred to in the musical.

When the New York Times reported on Oklahoma on November 10, 1907, it noted a total population of 1,500,000 people; one week later, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Oklahoma the brand-newest state in the Union.

The musical Oklahoma! is set in the Verdigris Valley, in the heart of Indian Territory, within a few miles from the town of Claremore, a few years after the turn of the century. (Claremore is about 30 minutes northeast of Tulsa, which would only become a major city after an oil boom in the 1910s.) By 1900, Claremore had a population of 855, a rail station, a post office, and several hotels (and was the birthplace of Will Rogers in 1879). It’s worth taking note that, despite (or perhaps because of) the relocation discord with the Indigenous nations, the word “Indian” is never mentioned once in Oklahoma! proper – the stage directions reveal the setting simply as “Indian Territory. Now Oklahoma” – and although Aunt Eller’s farm is nearly at the junction of the Cherokee, Creek and Osages Nations, there is never even a passing reference to tribal culture. (To be fair, there is practically no mention of Indigenous people in Lynn Riggs’s original play, either.)

During the decade-and-a-half of the Oklahoma Territory’s existence, the momentum among the settlers toward statehood was nearly relentless – and full of obstacles. Its inhabitants tended to be Democratic by party affiliation and Republican congressmen in Washington had no intention of adding a Democratic state to the Union. More complicated was whether the Oklahoma Territory would be admitted to the Union along with the Indian Territory, or on its own, or as two separate entities; years were spent wrangling various details and the policies.

What the new Oklahomans wanted in a brand-new state was pretty obvious – they desired not just a feeling of local pride but the protection of a federal jurisdiction and access to federal funds. These included a more responsible and accountable judicial system and money to build schools and railways; each of these concerns are reflected, one way or another, in the musical. The movement for statehood culminated in June 1906 with the passage of the Enabling Act, which set in motion the drafting of a state constitution.

That act mandated that freedom of religion was to be preserved, polygamy and plural marriage were not, and alcohol would be prohibited for twenty-one years. Among other provisions was the establishment of public schools, which were to be nonsectarian and were to be conducted in English. The right to vote was extended to all males “of any race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Oklahoma was to have five representatives in Congress, in addition to the customary two senators. When the New York Times reported on Oklahoma on November 10, 1907, it noted a total population of 1,500,000 people; one week later, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Oklahoma the brand-newest state in the Union.

Two other parts of the southwest – Arizona and New Mexico – would also be incorporated into the Union as states within a few years. The heady promise and entitlement of westward expansion – known as Manifest Destiny – would have been embraced without ambivalence during wartime in 1943 when Americans demonstrated a particularly strong solidarity for their values. In the musical, before he sings the title number, Curly has a speech that would have been affirmed by an audience motivated and energized by the mainstream American traditions of the previous half-century:

"Oh, things is changin’ right and left! Buy up mowin’ machines, cut down the prairies! Shoe yer horses, drag them plows under the sod! They gonna make a state outa this, they gonna put it in the Union! Country a-changin’, got to change with it!”

Interestingly, the idea of the title number was suggested to Hammerstein by one of the musical’s producers, Theresa Helburn. She instinctively felt that there needed to be something in the second act that catalyzed and coalesced what these eager young settlers of the 1900s stood for – and by extension, the young men and women fighting abroad in 1940s: their collective sense of belonging. Helburn tried to articulate it thus: “something about the land.” While the show was in its tryout phase, under the title Away We Go!, the song was arranged as a choral number and lifted the entire show off the ground. In its final iteration, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s song “Oklahoma” summed up the ethos of the show so perfectly – “we know we belong to the land/ And the land we belong to is grand” – that the musical gained a new title (with an exclamation point) and a new reason for being, and never looked back.

Click for more.

Time and perspective have been kinder to the show than to some of the more complicated values that lie beneath the concept of Manifest Destiny; even in the 1907 article about Oklahoman statehood, the New York Times concluded with: “The most pathetic incident in the birth of the new State is the passing of the Indian.” Those complications hardly belong to the history books of the past. As recently as July of 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that much of eastern Oklahoma – particularly the Muscogee (Creek) Nation – remain a reservation, under Native American jurisdiction for its judicial system, not under jurisdiction of the federal government. The Court upheld the original treaties made between the federal government and the Indigenous tribes in the 19th century: “Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

Oklahoma (the state) and Oklahoma! (the musical) are part of our complex national psyche. Obsession, rivalries, revenge, gunslinging, Manifest Destiny, frontier justice and death have always been part of Oklahoma!, even if those thornier aspects have often been papered over in various productions and films over the years. But, much like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie novels, Oklahoma! is resilient and resonant enough to contain many contradictions about who we are as a nation, certainly in terms of its buoyant view of western expansion. As Aunt Eller – in many ways the heart and soul of the musical – puts it: “You cain’t deserve the sweet and tender things in life less’n you’re tough.”

Oklahoma! has always been tender and tough.

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.