IT’S NOT JUST WHAT THEY DID – IT’S WHAT THEY DIDN’T DO: Oklahoma! and Musical Narrative

Perhaps if the creative team behind Oklahoma! had liked George Church’s second-act specialty tap number just a little bit more, the history of the American musical would have been written differently.

Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! has been justly recognized as a trailblazer (or perhaps more fittingly as entering a “new frontier”) for the role it played in evolving the narrative musical on Broadway, back in 1943. (Since the 1950s, critics have also referred to this kind of show as an “integrated” musical, but it’s a term that, in my view, is no longer relevant or helpful.) A narrative musical, as the name implies, places a priority on telling a narrative – a story with a beginning, middle, and end. What made Oklahoma! groundbreaking as a narrative musical was not simply that it told a story (dozens of opera, operettas, and musical comedies had done that for decades), but the ruthless discretion that Rodgers, Hammerstein and their collaborators deployed towards dialogue, music, lyrics, staging, dances and décor in order to tell that story. Like Michelangelo chiseling away all the superfluous marble that wasn’t essential to his statue, the creative team was boldest in paring away all the obstacles that got in the way of their story.

The American musical theater tradition had been around for less than forty years when Oklahoma! premiered. That tradition, such as it was, which Rodgers & Hammerstein inherited, was largely a non-narrative one, i.e., revues and loosely constructed vehicles for singers, dancers and comedians. Florenz Ziegfeld and his annual Follies were the gold standard of this form, but he was by no means the only purveyor of these incidental (and ultimately evanescent) charms. Audiences from the 1900s through the 1930s delighted in ebullient evenings on Broadway with a succession of leggy chorus girls, playful tunes, goofy comedians, sultry sirens and a battalion of tap dancers. If any of those elements were halfway decent (preferably all in the same show), the producer probably had a hit on his hands; audiences demanded no more coherence or continuity than we might ask today from Saturday Night Live, a rock concert, or a “Greatest Hits” album.

That said, during the four decades before Oklahoma!, there were a handful of shows that demanded more of themselves and of their audiences; the common denominator of these musicals was that their creators used songs, not as amiable distractions, but as a way of advancing the plot. The best of these are Show Boat (1927: Hammerstein and Jerome Kern); Of Thee I Sing (1931: George and Ira Gershwin, book by George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind); and Pal Joey (1940: Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, book by John O’Hara). Each of them has extraordinary merits and yet each of them falls a bit short in terms of deploying a seamless narrative. They were still bound, in different ways, to the conventional expectations of musical comedy.

Show Boat was produced by Ziegfeld, who was admittedly intimidated by the seriousness of the show’s epic storyline. Since he held the purse strings, he was able to compel the creators to add a little more song-and-dance and some bigger production numbers; these numbers may have amused audiences at the time, but were detours from the main storyline involving a multitude of characters. Such obligations forced Hammerstein to wrestle with the show’s already unwieldly second act for years in subsequent productions and revivals.

Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! has been justly recognized as a trailblazer (or perhaps more fittingly as entering a “new frontier”) for the role it played in evolving the narrative musical on Broadway, back in 1943.

Of Thee I Sing was pure musical comedy and although it rendered a complex storyline filled with satire on contemporary politics, it was also a vehicle for a famous stage comedy duo of the time – William Gaxton and Victor Moore – and tailored much of its routines around them. There were also scenes built around both leggy chorines and tap-dancers (although, to be fair, those conventions were being mocked in the show). Pal Joey had a fairly streamlined narrative, but given its nightclub setting, there were plenty of opportunities for flashy non-narrative numbers and one song, “Zip!”, a striptease spoof sung by a reporter – marvelous though it is as a specialty number – could easily be cut without altering the show whatsoever.

It should also be noted that the legendary 1939 movie musical, The Wizard of Oz, is a near-perfect example of musical narrative, with no significant deviations from the main story of Dorothy’s journey to Oz and back. (It also has an extremely clever framing device with the Kansas inhabitants reappearing as characters in Oz.) Perhaps this is because its creators were accomplished Broadway hands: E. Y. “Yip” Harburg and Harold Arlen.

The evolution of Oklahoma! wasn’t so much a conscious attempt to build on these narrative precedents, it was more of a personal response from Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II to the basic simplicity and sincerity of Lynn Riggs’s Green Grow the Lilacs, the original source material. The various junctures in their respective careers were influential as well. Rodgers had come off a series of smarty-pants contemporary musicals in the early 1940s, and he and Hart created a vehicle for the hoofer/comedian Ray Bolger in 1942: By Jupiter, set in ancient Greece. The homespun honesty of Riggs’s play would have been a welcome challenge for the team, but the material did not inspire Hart’s sense of cosmopolitan sophistication; Rodgers sought out a new partner. Hammerstein was also at a crossroads. Few librettists commanded as much respect along Broadway as Hammerstein, but he confessed himself devoid of inspiration. Several sojourns in Hollywood did little to engage his creativity and his primary genre of musical theater – the operetta – was out of step with the times: “Operetta is a dead pigeon,” he wrote in the early 1940s, “and if it’s revived, it won’t be by me.”

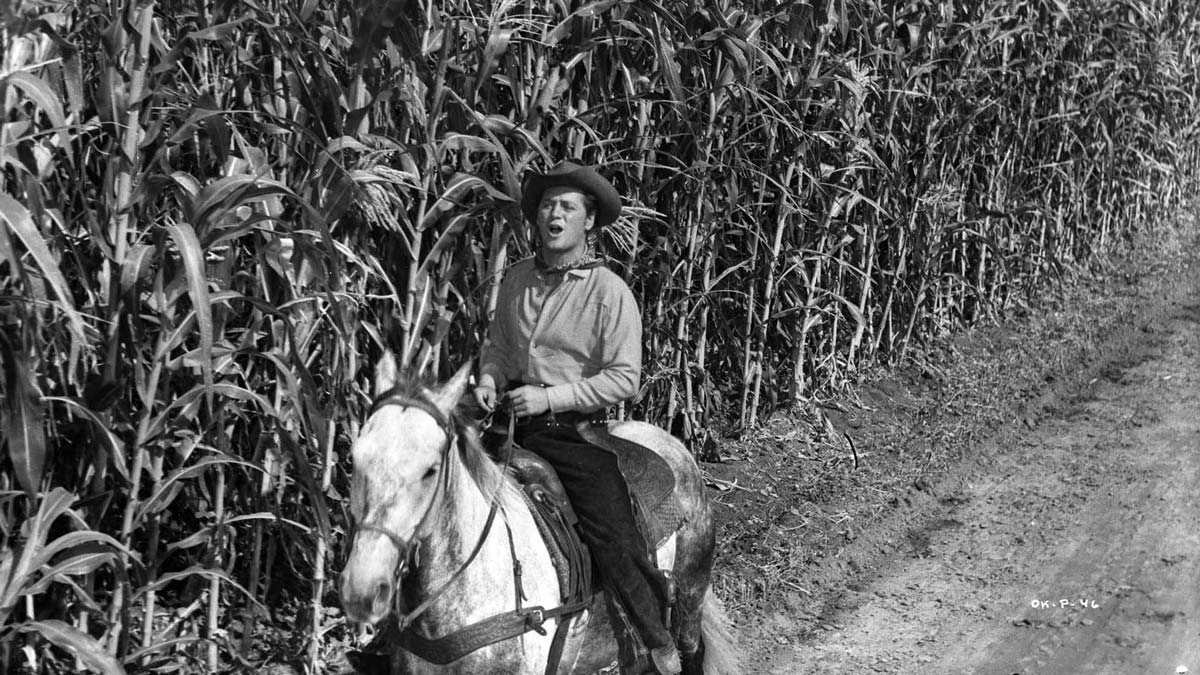

A song about the bright gold haze on an Oklahoman meadow, begun offstage and continued as a serenade by a bowlegged cowboy to a mature lady working away at a butter churn on her porch, may strike few people in the 21st century as revolutionary, but compared to what else was playing at the time, it was.

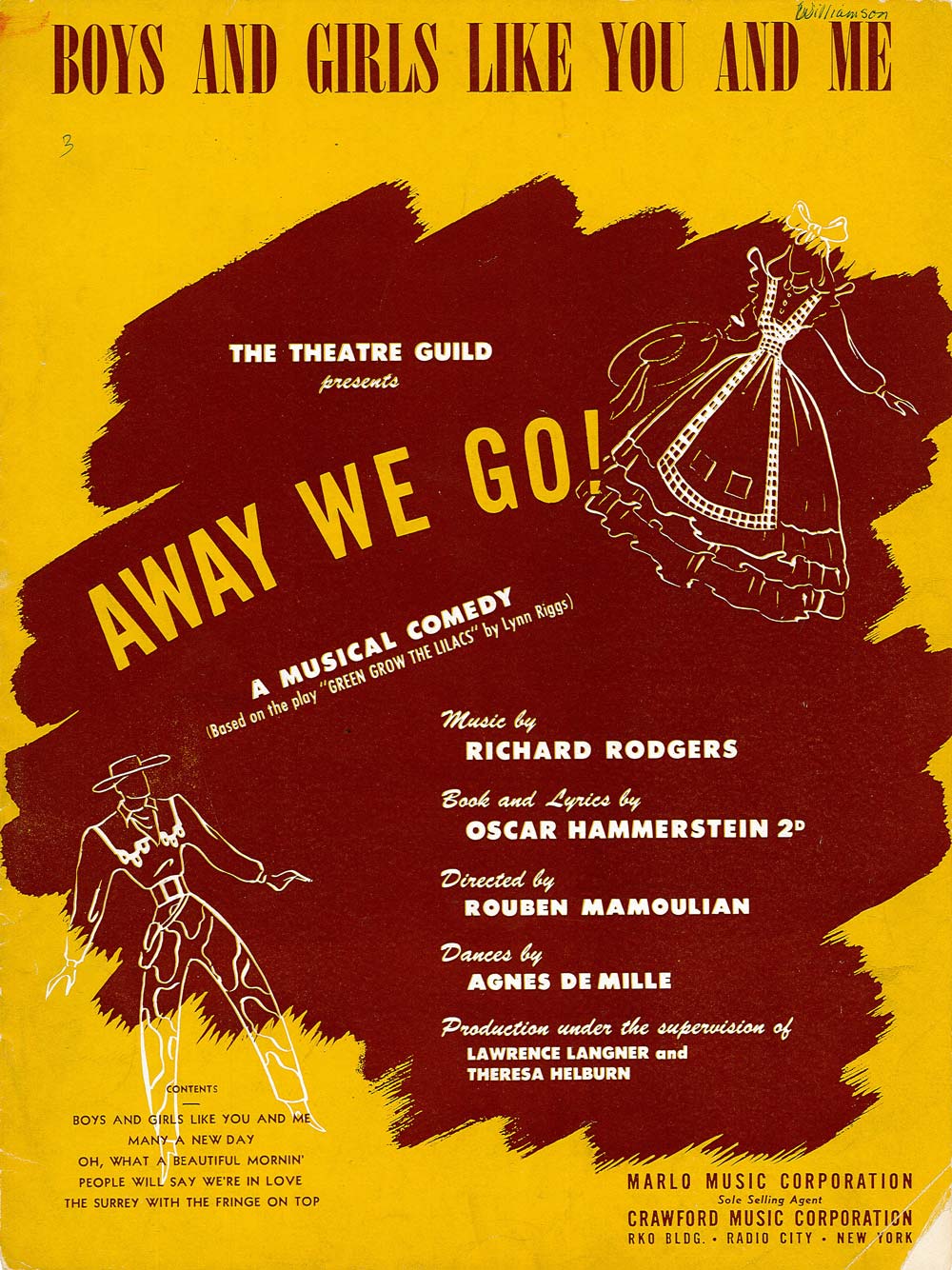

The circumstances that launched the project that became Oklahoma! (known throughout most of its creative genesis as Away We Go! – a title that excited no one’s enthusiasm) were a combination of desperation and inspiration. The idea for a musical version of Riggs’s play was the brainchild of the prestigious Theatre Guild under the management of Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner. They had produced the original play back in 1931, but by 1942, the company was in serious danger of folding; faced with continually bouncing checks, they saw a new musical as a way of bouncing back. The Theatre Guild didn’t have enough money to produce anything spectacular, while at the same time, Rodgers & Hammerstein, forging a new partnership, had no interest in writing anything complicated.

The conventions of the era cast a long shadow over the initial stages of their collaboration: “The first problem that faced us involved a conflict of dramaturgy and showmanship,” wrote Hammerstein. “The traditions of musical comedy [demanded] that not too long after the rise of the curtain, the audience should be treated to one of musical comedy’s most attractive assets – the sight of pretty girls in pretty clothes moving about the stage, the sound of their vital young voices supporting the principals in their songs.” Every idea that the songwriters tossed back and forth to each other seemed stale, contrived, or improbable. “[After] passing through phases during which we would stare silently at each other, unable to think of anything at all, we came finally to an extraordinary decision. We agreed to start our story in the real and natural way in which it seemed to want to be told.”

They started their story with one of the most unexpected opening numbers in Broadway history. A song about the bright gold haze on an Oklahoman meadow, begun offstage and continued as a serenade by a bowlegged cowboy to a mature lady working away at a butter churn on her porch, may strike few people in the 21st century as revolutionary, but compared to what else was playing at the time, it was. Hammerstein put it succinctly: “Having met our difficulty by simply refusing to recognize its existence, we were ready to go ahead with the actual writing.”

The first act of Oklahoma! saunters along its low-key way, introducing the primary love story between the cowboy, Curly, and the object of his affection, the reluctant, ambivalent Laurey; contrast enters the narrative with the secondary couple, Will Parker and the extremely capricious object of his affection, Ado Annie (Will was an original creation of Hammerstein’s); conflict arises with the appearance of the malevolent farmhand, Jud, who also seeks Laurey’s romantic attention. Surveying these comings and goings with wry wisdom is Aunt Eller, the mature embodiment of practicality and common sense.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Oklahoma!’s narrative structure is not only the way that all of the initial plot passes in front of Aunt Eller’s porch, it’s also that the first scene of the first act takes up 40% of the entire show. In addition, more than half the score’s songs are introduced in that first scene. No musical had done anything quite like that before; typically, back then, a show would alternate between full scenes and “in-one” scenes (in front of a show curtain so that scenery could be changed) with a frenetic pace and reckless abandon to keep the audience entertained. In Oklahoma!, the narrative of the show dictated its pace; to paraphrase Hammerstein, the writers refused to recognize the existence of this musical comedy convention.

Another example of the show’s respect for narrative is the way that Hammerstein constructed the songs and their relationship to the dialogue between characters. It’s not something one considers much, as songs such as “The Surrey from the Fringe on Top” and “People Will Say We’re in Love” have been enjoyed for decades as self-sufficient songs on various cast albums and popular recordings but within the context of the production, nearly all of the songs in Oklahoma! are interrupted by, or carried through by, sections of dialogue. Dialogue is woven through lyrics even in such standards as “Surrey” and “People Will Say” – they are not stand-alone numbers. Of course, Hammerstein, as book writer and lyricist, was in complete control of all the words, but he also knew better than anyone in the business how to move from dialogue to the emotional expression of song and – importantly – how to move back again.

Still, as Rodgers & Hammerstein dove into writing the show, the attraction of a big self-sufficient production number was tempting. They had each stood at the rear of the orchestra in enough theaters for enough of their respective shows to watch enough audiences go bonkers for enough show-stoppers to realize how effective they could be. Old habits die hard. When confronting the act one closer of Oklahoma!, Hammerstein drafted an initial treatment for a ballet that he called “bizarre, imaginative and amusing, never heavy.” It included some expressionistic moments, such as Aunt Eller as a circus rider in pink tights and Jud dancing in a costume made of knot holes. The treatment was largely focused on the rivalry between Jud and Curly (which, to be fair, the audience already had experienced). The scenario was indeed “imaginative”—maybe too much so; it would certainly have sent the audience out for intermission on a high note.

Here’s where Rodgers & Hammerstein were fortuitous in their collaborators. Agnes de Mille, a choreographer with a rigorous penchant for storytelling making her Broadway musical debut with Oklahoma!, summoned up her courage (and psychological acumen) and persuaded Hammerstein that a serious dream ballet that focused on Laurey and explored her conflicted subconscious would not only be dramatically powerful but would carry the narrative forward by going inside the lead character’s psyche. This proved not only stunning to watch but ended the first act on a question mark – perhaps not conducive to a good mood, but always a provocative way to get an audience to return to their seats after intermission.

The creative team was guided by an esteemed strong-willed Armenian director named Rouben Mamoulian, who had not only directed Porgy and Bess on stage, but a groundbreaking musical film by Rodgers and Hart, Love Me Tonight, back in 1932. Mamoulian proved to be a tortured referee in the contest between musical comedy convention and the demands of narrative. On one hand, he was a natural showman and wanted to make sure the second act ended with a “bang.” However, his several attempts to amp up the proceedings during tryouts came to naught: a display of fancy rope tricks as a specialty act during Alfred Drake and Joan Roberts’s (Curly and Laurey) rendition of “Oklahoma” nearly resulted in their getting decapitated and an attempt to release a flurry of pigeons at the conclusion of the final wedding party was a disaster; they flew into the rafters of Boston’s Colonial Theater and were never convinced to come back down.

Still, when all was said and done, Mamoulian was not one to waste an audience’s time. Rodgers and Hammerstein had added a second act duet for Curly and Laurey entitled “Boys and Girls Like You and Me,” but the song itself (though lovely) was so dramatically inert that the director tied himself in pretzels trying to stage it in a compelling fashion. Declaring that any further work on it would send him to an insane asylum, he asked that it be cut. Rodgers and Hammerstein obliged and inserted a short reprise of “People Will Say We’re in Love” and the second act went on its merry and expedient way.

Which brings us to George Church and his second-act tap specialty. De Mille was a dynamo as a choreographer, providing not only moments of engaging narrative, but also some spectacular moments that featured members of her ensemble. The “Dream Ballet” showcased a few of them, as did “The Farmer and the Cowman.” By the time Oklahoma! reached its New Haven tryout, the performance of the title number was built around a dynamic tap-dancing specialty solo performed in the middle of the song by dancer George Church (he also portrayed Jud in the “Dream Ballet”). Church’s solo was such a big deal that he was given his own credit line in the program. New Haven audiences ate it up; it stopped the show. But that was the problem and that’s where Oklahoma! diverged from all its predecessors: the specialty number stopped the show – so out it went. Church was deeply unhappy, understandably, but the creative team knew and trusted that any element which diverted Oklahoma! from the natural conclusions of its narrative became an obstacle, no matter how much the audience enjoyed it. Rodgers, Hammerstein, De Mille, Mamoulian – they put their faith in the hope that the audience would enjoy the story even more.

Successful musicals are created out of an ineffable alchemy: if we knew what made a successful musical and could bottle it, producers would be lined up along Broadway from the West 30s to the West 50s. Groundbreaking musicals are created out of that same alchemy, but with an additional element of trust that its creators know where they are going, that they share the same vision and vocabulary. As Rodgers once said about this kind of show, “the costumes look the way the orchestra sounds.” In the case of the narrative achievement of Oklahoma!, it has to be said that the sheer penury of its producers, the Theatre Guild, weighed heavily on the scale. They simply had no money – not for stars (who would have, perhaps, made their own demands of the creative team), not for elaborate scenic effects or production numbers, not even, really, for all those darned pigeons. Everyone would simply have to work together to tell the story – and the creative team understood that story. As Hammerstein put it in a 1948 letter to a European producer: “Oklahoma! is not an operetta [like] the ‘Beggar’s Student’ or ‘Prince of Pilsen.’ It is not a vehicle for deep-chested baritones to display their voices. It is a small human story, a sketch of characters, and a swift moving symbol of the spirit of the pioneer America about 1900.”

There have been very successful non-narrative musicals since 1943, such as Cats or Chicago (which still knock the audience out with their specialty dance numbers), but Oklahoma! invited its audience for a longer, more compelling journey – it asked its audience to hop inside a shiny little surrey with the fringe on the top and go along for the ride: don’t you wish it would go on forever?

And it has.

Laurence Maslon is the author of The Sound of Music Companion as well as Broadway to Main Street: How Show Tunes Enchanted America. He also is the host of the weekly broadcast/podcast “Broadway to Main Street” on the NPR affiliate WLIW-FM.